|

Fear, anxiety, and stress are all related emotional and psychological responses to perceived threats or challenges, but there are important differences between them. Fear is a natural and immediate emotional response to a real or perceived threat. It is a normal response to danger and is often accompanied by physical sensations, such as increased heart rate, rapid breathing, and sweating. For example, if you hear a loud noise in the middle of the night, you may feel fear because you perceive a potential threat. Anxiety, on the other hand, is a more diffuse and generalised emotional response to perceived threats or challenges. It often involves a sense of uncertainty or apprehension about future events or situations. Anxiety can be triggered by a wide range of stimuli, and it may manifest as physical symptoms such as restlessness, fatigue, or muscle tension. Stress is a physiological and psychological response to challenging or demanding situations. It is a normal response to situations that require increased effort, such as work deadlines or public speaking. However, chronic or prolonged stress can have a negative effect on physical and mental health. PERCEIVED THREAT OR CHALLENGE Fear = Immediate response to actual or perceived danger. ⬇️ Anxiety = Diffuse and general feeling of unease or apprehension ⬇️ Stress = Physiological and psychological response to demands or pressures In summary, understanding the differences between fear, anxiety, and stress can help individuals more effectively recognize and develop strategies to manage and cope with each one. Additionally, by recognising the signs and symptoms of these responses, individuals can seek appropriate treatment or support when necessary. Overall, understanding the differences between fear, anxiety, and stress is an important step in promoting emotional and psychological well-being. Kara Vermaak. Provisional Psychologist We all have thoughts, that’s part of what makes us human. Sometimes these thoughts are pleasant and helpful, but sometimes they’re unhelpful and unpleasant. Our natural response may be to want to get rid of those unhelpful thoughts as soon as we can. Why would we choose to feel pain and discomfort? Unfortunately, trying to control these thoughts often has the opposite effect. They just keep coming back. Imagine you’re throwing a party. Everyone is having a great time, but there’s this one unwelcome, uninvited and somewhat obnoxious person who shows up at your house. You’ve decided to take charge, and show them out the door. But despite your best efforts to get rid of them, they keep finding a way back into your house. You become increasingly agitated as you see them annoying your guests, but they just won’t stay away. You soon realise that trying to get rid of them is futile. So what could you do instead? 1. Recognize the guest: Just like you would recognize the unwelcome party guest, recognise the unhelpful thought without judgment. Acknowledge that it's there and that it's causing you discomfort or distress. 2. Accept the guest's presence: Rather than trying to force the guest out, accept that they're there for now. Recognize that, just like the guest at the party, the unhelpful thought may stick around for a while, even if you don't want it to. 3. Observe the guest without judgment: Instead of getting caught up in the guest's behaviour, observe them without judgement. Notice what they're doing and saying, but focus on what you’re doing instead. 4. Let the guest be: Just like you might let the unwelcome party guest be, let the unhelpful thought be. Don't try to change it or control it, just observe it and let it exist without getting caught up in it. Eventually, you find that you’re so busy having fun, that you’ve forgotten all about the unwelcome guest, and your friends don’t seem too bothered by them either. After a while, they get bored, say goodbye and leave. Remember that just like an unwelcome party guest, unhelpful thoughts may arrive uninvited and unwanted, but they don’t have to define your experience. By accepting their existence and letting them be, they eventually pass by as just another thought. Book an appointment with Kara or one of our friendly psychologists

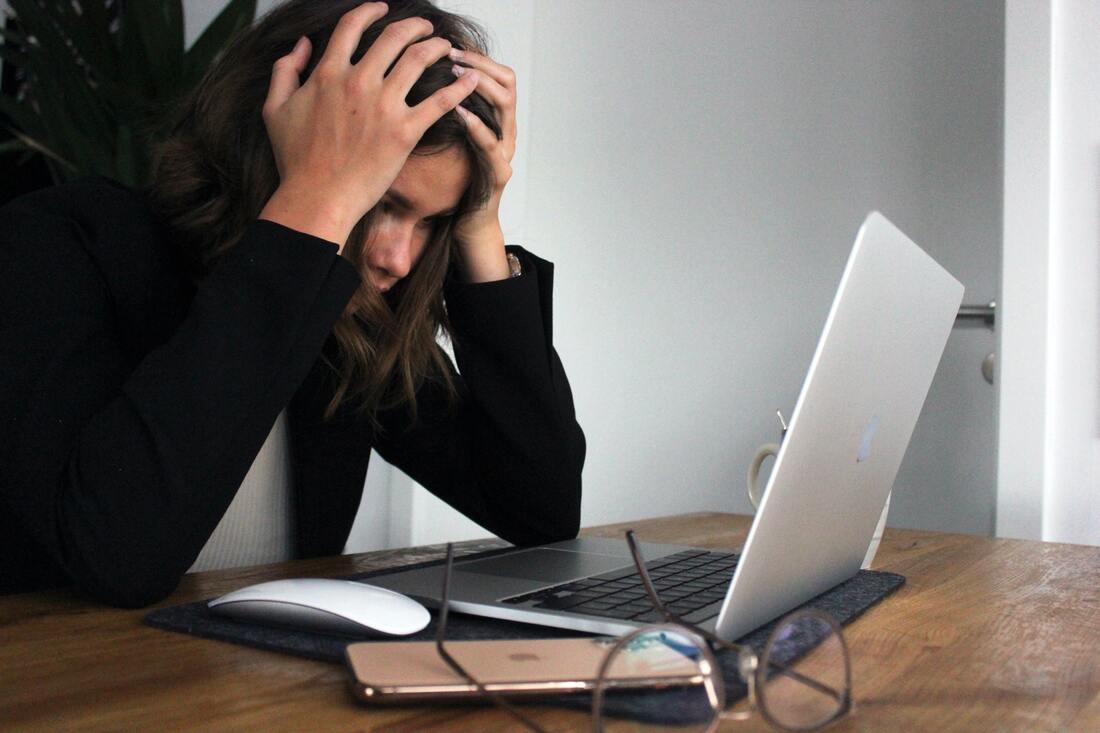

Are you feeling physically and emotionally drained? Do you find yourself disconnecting from family or friends? You may notice yourself increasingly needing to take time off work, or lacking the motivation to complete routine tasks.

Sound familiar? If so, you may be experiencing burnout. Burnout is about feeling not enough. It is about feeling empty, devoid of motivation, and beyond caring. Here are some ways to prevent feeling burnt out… 1. Be aware of what you can and cannot control, and focus on problem solving the things you can control Put things into perspective! We often feel demotivated and deflated when things don’t go to plan, however it’s important to remember that we don’t have control over absolutely everything. We may encounter obstacles that were unforeseen and unavoidable. Life happens. Focus on problem solving the things you can influence, and you will feel more accomplished. 2. Simplify your day, and know your limits Ask for help and learn how to say “no”... and mean it! We can’t do everything for everyone, despite what we think! It is important to maintain boundaries with family, friends and/or colleagues. Sometimes you just need to switch off. You can't be available to everyone at all times! 3. Write a to-do list It is important to start each day with a purpose. Each evening, list three tasks that you will aim to complete during the course of the following day. Checking off tasks each day is one of the best ways to feel accomplished and satisfied. 4. Practice mindfulness It is important to take time out of your day to give yourself the chance to ground yourself and come back to the present moment. It's important to routinely take time out to breathe and re-centre. Regular practice will help you feel more in control and be better able to make good decisions. 5. Remember to schedule self care into your week I’m sure you’ve heard it all before, but really, how often you you deliberately schedule in self care to your routine? I’m sure like many, we have good intentions to carve out time for ourselves, but we let other priorities often get in the way. You are doing a disservice to your loved ones by not looking after yourself! Keep it simple...exercise regularly, maintain a well balanced diet, start a new hobby, learn an instrument, keep up with social connections, the options are endless! If this is sounding all too familiar are you are wanting some extra support, please book in an appointment with one of our clinicians Many people tend to find it difficult to differentiate between fear, anxiety and stress. Although all experiences are quite normal, it is important to know the difference so you can seek the most appropriate support if necessary.

Here are a few defining features of the three experiences:

Fear and stress:

Anxiety:

There are three components that contribute to feeling anxious:

We have fear and anxiety in non life-threatening situations because of the way we interpret the situation. If you are struggling with fear, stress or anxiety and are needing some support, please contact the clinic to book in an appointment with one of our psychologists Alyce Galea, Psychologist Urge surfing is a helpful technique when your way of dealing with stress and overwhelm is particularly unhelpful, unhealthy or harmful.

For example, if your automatic response to feeling overwhelmed is to over eat, use substances or self harm, then this technique is an important one to learn and practice. The goal of this technique is to delay acting on the urge, until the feeling of the urge goes away. One way to think about an urge is like the urge being a wave and you being a surfer. A surfer doesn’t fight against the wave or run away from the wave, instead, they ride the wave until they reach the shore. Urge surfing is about riding the emotional wave. Not fighting with the need to resist the urge, and not giving into the urge. Simply noticing the urge and letting it run its course. Mastering this technique will take some time, patience and practice. But once you are able to get the hang of it, you’ll be better able to regulate your emotions in a helpful and healthy way. The easiest way to practice urge surfing is to set timed intervals between when you first notice the urge, and when you allow yourself to act on the urge, and then do something during that time to distract yourself and keep you busy. Things you could do to distract yourself could be to:

The more you practice this skill, the easier it will be for you to ride out the urge wave and not let the urge dominate your thoughts. If you are struggling with managing unhelpful thoughts or urges, please book an appointment with one of our psychologists Alyce Galea, Psychologist Emotions such as fear, anger, grief and many others can negatively affect us long after the original event that caused them.

When our body fails to “let go” of these emotions we can find ourselves with unexplained hatred, self-sabotaging behaviours, destructive beliefs, phobias and many chronic physical problems. Why Do People Bottle Up Their Emotions?

What Happens When You Pent Up Your Emotions

Ways to release bottled up emotions

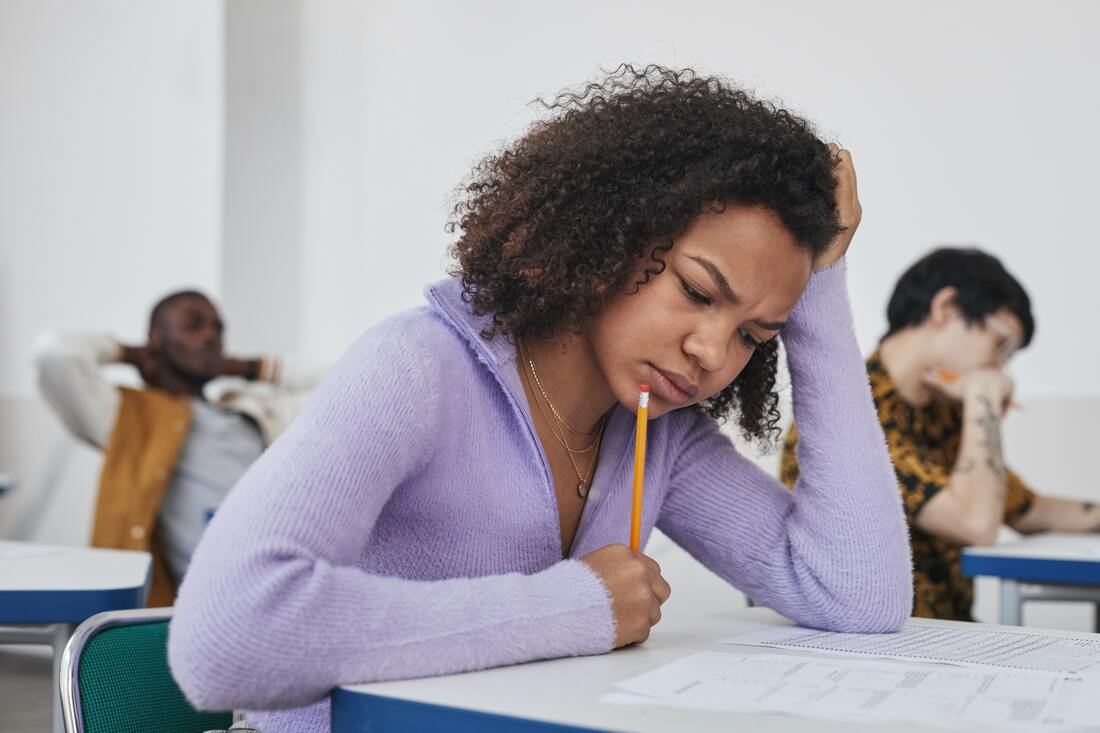

Book an appointment with one of our friendly psychologists for more support Alyce Galea, Psychologist It is most likely the time that most students dread...Exam time!

Although for some people, stress can motivate them to be more organised and devote more time to study, for others, prolonged stress can be counterproductive and debilitating. For a lot of students, exam time can be a daunting and stressful period, but it doesn’t have to be! Here are some tips that might help you to manage stress around exam time... 1. Think about why you are stressed:

2. Take time to plan:

3. Make self care a priority

4. Rest

5. Set good boundaries

Above all, remember that this period of stress is only temporary! If you continue to feel stress or anxious after the exams, it might be helpful to speak to someone (a teacher, family member, friend, psychologist) about what you can do to manage these feelings next exam period. Book an appointment with one of our psychologists for more support with school issues and exam stress Consider your general wellbeing as a bucket.

Whenever you experience a situation that causes stress, you pour a metaphorical glass of water into that bucket. What will happen over time if you don’t actively address those stressors and release water out of that bucket? It will overflow! So if that bucket represents our emotional health, the act of the bucket overflowing represents times where we feel overwhelmed, out of control and exhausted. Our goal is to find ways of releasing some of that stress on a regular basis, so that our bucket never overflows. If you or your child require support in managing stress or anxiety, please contact the clinic to book in with one of our friendly psychologists You might be able to recall a time where you’ve felt...

- emotionally drained; - you’ve become more distant at work; - and you’ve started to feel like nothing you do is ever good enough. Does that sound familiar? Now, more than ever, employees are reporting high levels of burnout. You’re exhausted. We all are. I encourage you to focus on nourishing your body. Notice what it needs and respond accordingly. Think about the last week... How mindful have you been about what you have put into your body? Have you made it a priority to move your body? How kind and compassionate have you been to your body? Have you taken the time to really treat and care your body? If you are feeling burnout and require therapeutic support, we have immediate availability with for adult clients Sometimes it’s incredible to think about what our body can take during times of stress. We can continue to ‘soldier on’ during busy and stressful life events, while juggling work, family, friends, finances, and the list continues. Being a parent can bring about some of the most stressful times of our lives. We can find that we become exhausted, and resentful, and while juggling all of those balls, it often feels like what we are doing is just not good enough.

Most of the time, we find that we can do this OK, but ‘burning the candle at both ends’ over a prolonged period of time can have a significant and detrimental effect on our health and well-being. There are 6 specific areas of life/work that have been identified as contributing to stress and burnout. A feeling of a lack of control, and not having a say in what is going on can be created by the uncertainty or ambiguity of a situation. When your core values are in conflict with someone or with an event, this can be very stressful. This may be an increase in work demands that is impacting on family time. Feeling taken for granted or feel like you are not being appreciated can be a common feeling for all parents and can be a contributor to those feelings of resentment. With demands of home and work, it can often feel like it is impossible to prioritise. Everything seems like it is the most important task, and it can feel endless. Feeling on top of things can be even harder if you feel like there is something that is unfair about what is in front of you. Finally, if you feel like there is a breakdown of in the connection between your loved ones, it can feel incredibly stressful and isolating. As the stress continues we find that we continue to get sick. This is because our immune system is being weakened, and we are more vulnerable to illness. It also takes us longer to feel better when we are stressed. We also feel a lack of energy or fatigued. It might mean coming home from work and being unable to muster up the energy to do extra things like exercise, or hobbies that you enjoy. To help reduce the chance of burnout, it takes practise to remind ourselves to be “good enough” and not perfect. This is not always easy, and it much easier said than done, but it helps us to remember the good and positive things that we are doing and achieving, rather than the things we are not doing, or missing. Feeling gratitude is a major contributor to happiness, while perfectionism can be linked to depression and anxiety. For support in how to feel less stressed and burnt out, book in with one of our friendly psychologists Sometimes it’s incredible to think about what our body can take during times of stress. We can continue to ‘soldier on’ during busy and stressful life events, while juggling work, family, friends, finances, and the list continues. Being a parent can bring about some of the most stressful times of our lives. We can find that we become exhausted, and resentful, and while juggling all of those balls, it often feels like what we are doing is just not good enough.

Most of the time, we find that we can do this OK, but ‘burning the candle at both ends’ over a prolonged period of time can have a significant and detrimental effect on our health and well-being. There are 6 specific areas of life/work that have been identified as contributing to stress and burnout. A feeling of a lack of control, and not having a say in what is going on can be created by the uncertainty or ambiguity of a situation. When your core values are in conflict with someone or with an event, this can be very stressful. This may be an increase in work demands that is impacting on family time. Feeling taken for granted or feel like you are not being appreciated can be a common feeling for all parents and can be a contributor to those feelings of resentment. With demands of home and work, it can often feel like it is impossible to prioritise. Everything seems like it is the most important task, and it can feel endless. Feeling on top of things can be even harder if you feel like there is something that is unfair about what is in front of you. Finally, if you feel like there is a breakdown of in the connection between your loved ones, it can feel incredibly stressful and isolating. As the stress continues we find that we continue to get sick. This is because our immune system is being weakened, and we are more vulnerable to illness. It also takes us longer to feel better when we are stressed. We also feel a lack of energy or fatigued. It might mean coming home from work and being unable to muster up the energy to do extra things like exercise, or hobbies that you enjoy. To help reduce the chance of burnout, it takes practise to remind ourselves to be “good enough” and not perfect. This is not always easy, and it much easier said than done, but it helps us to remember the good and positive things that we are doing and achieving, rather than the things we are not doing, or missing. The feelings of gratitude are a major contributor to happiness, while perfectionism can be linked to depression and anxiety. Read Part 2 of this blog post to learn how to help bring your focus back to the positive. Megan Mellington, Psychologist As a parent, we will undoubtedly encounter moments of frustration towards our children. It could be awoken by the simplest of circumstances, such as needing to repeat ourselves like a broken record, intervening with siblings squabbling over a toy, or because we are stressed by other things and our tolerance for managing challenging behaviours is limited. However, as many of you might already have experienced, when we respond with anger this often only escalates the situation with our child, and they too may then respond in a similar manner. While many of us have regrettably resorted to shouting, questioning or punishments out of anger, what is important to remember, first of all, is that you are human. Anger is a normal part of the spectrum of human emotions. Anger isn’t bad, it reminds us that we are passionate about something like perhaps wishing to raise respectful, emotionally regulated and empathic little humans. So when less than desirable behaviours are observed in our children, we want to help them develop ways to self-manage, through teaching and implementing boundaries. Sometimes though, when we have been teaching and redirecting our children all day, our waning tolerance for their tantrums or perceived “defiance” can move us to anger. This article aims to outline some tips about how to tame our own “angries” so that you can engage with your children in a mindful and empathic way. I've previously shared Dr Dan Siegal's video explanation of what happens in the brain when we get angry and how the thinking part gets shut down. So how do we get our “thinking brain” back online so that we can respond in a more helpful way for our children? The following are several brief tips I often use in parent consultations to support this process:

Repair involves:

We can’t always be an emotionally regulated parent, and we shouldn’t expect this of ourselves. Even if we do take our anger out on our children, there are many things we can do to minimise the likelihood of this happening in future. If we can tame our “angries” by recognising our emotional state, taking a pause before responding, and regulating ourselves before attempting to regulate our child, we are modelling adaptive and healthy ways of managing anger.

By Jessica Cleary, Psychologist "Your normal may be their magic." It's all about perspective mamas! This video is sure to pull at your heart strings as you watch vlogger Esther Anderson's moving piece of her day from the perspective of both herself and then her young daughter. After watching, you can't help but reflect on the way you sum up your own days. Do you hold on to the magical moments and celebrate them? Or do the frustrations leave a more lasting impression? Let this be today's challenge: Notice and hold on to the magic. Breathe in the giggles and the sillyness, the cuddles and the kisses. Breathe out the tantrums and tears, the defiance and backchat. See if it makes a difference on the way you feel. There's a good chance it will!

by Melissa Bailey, Psychologist Anxiety is one of the most common childhood disorders. Most commonly a child will experience one of the following forms of anxiety:

Some of the ways anxiety may present in your anxious child:

The good news is that anxiety can be managed through therapy to learn how to decrease those worrying thoughts, but you as a parent or caregiver can also help your anxious child by teaching them to calm down and relax their bodies and minds. One technique that you can teach to your anxious child to help them relax is Progressive Muscle Relaxation (PMR). Often when we experience worrying thoughts and events our bodies will respond with muscle tension. This tension we feel can be uncomfortable making it difficult to relax and even go to sleep at night. PMR is the process of scrunching up different muscle groups for a few seconds and then releasing the tension. This is done in part so that we can identify the areas that we hold the most tension and also so that we can distinguish between tension and relaxation. Here are some basics you can try to help your child using Progressive Muscle Relaxation: Preparation:

What to say: "Take some deep calming breaths in through your nose and out through your mouth... Imagine your tummy is a big balloon and when you breathe in the big balloon is filling with air, and as you breathe out, the air is slowly escaping and the balloon becomes small again. Now...squeeze your toes and feet into a tight ball... hold this... (five seconds)... now relax...let them go loose. Tighten the muscles in your legs by pointing your toes...hold the muscles tight...(wait five seconds)... now let go and feel your legs go as loose as cooked spaghetti. Let's focus on your tummy now. Tense the muscles in your tummy by squeezing it in... hold this... (wait five seconds)...now relax...notice how good your body feels. Lift your shoulders as high as you can, bringing them up to your ears...hold this... (wait five seconds)...now relax....breathe in.... and breathe out... Next you can tense your arms and hands, by stretching them forward and tightening your hands into a tight ball, like you are squeezing a lemon...hold this... (wait five seconds)...now let your arms go floppy like cooked spaghetti...notice how relaxed they feel... Let's move to your face...tense your face by scrunching up your whole face...wrinkle it up as hard as you can...hold this... (wait five seconds)...now relax. Take another deep, calming breath in through your nose and out through your mouth... When you are ready, gently open your eyes and notice how good and calm your body feels." The following resources can further assist your child to relax using Progressive Muscle Relaxation:

New Year's resolution check in: Two simple steps to reduce stress and improve family relationships!10/1/2017

This time of year means different things for different people. It can be a time where families come together, a time when we are reminded of what might have been, a time of joy or a time of sadness. Emotions are heightened and stress levels can be high.

When our stress levels are running high it doesn’t take much to send us over the edge and get fired up about things that wouldn’t normally bother us.. To keep the rising stress at bay, here are 6 ways to reduce the Chirstmas chaos overwhelm.

The beauty about these ideas is that you can start immediately. They are simple and if you can introduce a couple of them to your days, you are sure to notice a difference in the way you feel. |

Categories

All

|

Hopscotch & HarmonyAt Hopscotch & Harmony Psychology, you can expect compassionate care and evidence-based guidance on your journey to wellness.

With clinics in Werribee and Belmont, as well as providing online counselling to clients who live throughout Australia, our dedicated team of psychologists and dietitians are committed to providing support to children, teenagers and adults. With a focus on understanding your unique needs, we offer tailored solutions to foster growth and resilience. Trust in our experience and dedication as we work together towards your well-being. Welcome to a place where healing begins and possibilities abound. |

Our services |

Contact usHopscotch & Harmony

Child, Teen and Adult Psychology Our Locations:

WERRIBEE: 1/167-179 Shaws Rd

BELMONT: 92 Roslyn Rd AUSTRALIA-WIDE: Online counselling |

Hopscotch and Harmony respectfully recognise the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people as the first Peoples of the continent now called Australia.

We acknowledge the Bunurong and Wadawurrung people of the Kulin Nation, the traditional owners of the land on which we work, and pay our respects to their Elders, past, present and emerging.

© 2024 Hopscotch and Harmony Pty Ltd

RSS Feed

RSS Feed