|

Just like an iceberg, when it comes to behaviour, there's so much more going on beneath the surface.

If we only pay attention to what we see, then we're not considering the full picture. You can't deeply understand an individual action without exploring at least some of those things that are rumbling below the surface. In fact, what goes on underneath is what gives rise to the behaviour that you see. Important motivators of the behaviour of young children include their needs and their feelings. What we don't see that influences behaviour includes things like a child's individual temperament, their emotions at the time, different sensory needs such as lighting and sound sensitivities, developmental capacity and limits, past experience that they bring into the moment, thoughts, internal sensations, executive functioning challenges that can affect planning, impulsivity, memory, physiological needs. All of these things we don’t see, are going to give rise to what we are actually seeing above the surface. When you start to feel challenged or frustrated by your child's behaviours, take some time to consider things on a deeper level. What could be going on below the surface? Our online Parenting Program explores child behaviour at great length with many strategies for you to use to navigate challenging parenting situations Tim Walker. Mental Health Clinician The Tiger Who Came to Tea is a children’s book. A young girl is surprised when a tiger enters the house at dinner time. Naturally this is an unexpected and difficult disruption! Rather than avoiding or resisting the tiger, the young girl offers it some tea. In fact, the tiger eats absolutely everything! The girl decides to accept him. The more food the tiger needs, the more she offers him. The girl and her family make room for the tiger, and finally it leaves. If we think of the tiger as anxiety knocking at the door, this story is a great example of using mindfulness and flexible thinking, individually and as a family, to manage anxiety. Whilst not based on mindfulness concepts, this story is a good analogy for sitting with anxiety in our lives, to better manage mental health. Seeing what is true, we hold what we see with kindness

What is behaviour? Behaviour is the way someone acts or conducts themself, especially toward or around others. When discussing children’s behaviours, we often find ourselves using the terms positive and negative behaviour or appropriate and inappropriate behaviour. Difficult Behaviours and why we act so quickly around them Children may at times display negative or inappropriate behaviour. As parents and adults, our first thought is to react to this behaviour straight away to try to cease it, because it is not considered appropriate in the current situation. The behaviour may be having negative effects on other people or their thoughts about the child or about us! Why do behaviours occur? Behaviour occurs for many reasons. The reasons we behave are called functions. There is often a function of every behaviour we see or do. The function is the Why. A person may be trying to gain someone’s attention, seek control of a situation or express their thoughts or feelings, none if which are wrong. The difficulty some children may encounter is in understanding how to use positive and appropriate behaviours instead. Noticing why behaviour is occurring is extremely important. We need to know why behaviour is happening and what a child wants, so that we can assist them to gain this in an appropriate way. When children have not independently clued onto how to behave in a positive manner, to get what they are after, they may continue to use negative behaviour because this is what they are familiar with… and maybe it has been working for them so far! Proactive and Reactive Methods Reacting to behaviour to try to stop or reduce behaviour after it has occurred is surprisingly called… a reactive strategy. Reactive strategies can include giving verbal feedback to a child or a fair and logical consequence occurring. Teaching a child a skill (like how to gain something in an appropriate way) before the child is in a situation is called using a proactive method. Using a proactive strategy gives a child the appropriate behaviour to use, and gives them the best chance to demonstrate a positive behaviour. They then have a better chance of what they want, which will encourage them to use the desired behaviour again. Do we need a more systematic game plan? If you find that a negative behavour is occurring again and again, and you can’t seem to redirect the behaviour to something more appropriate, these tips may help:

- Do they want someone’s attention? - Do they want to be in the ‘drivers seat’ of the situation? - Are they trying to communicate a thought or a feeling? - Are they trying to release frustration? - Are they trying to regulate themselves or self-soothe? - Are they trying to avoid something?

Knowing how to respond to behaviour, to encourage positive skills, and discourage negative behaviour is a tricky task. Every child is extremely different and will be encouraged and discouraged with varying methods of adult responses. If you have noticed difficult behaviours and would like some assistance to increase your child’s skills and to encourage positive behaviours, please contact us - we are here to help. Dr Dan Siegel is a neuropsychiatrist and pioneer in understanding the relationships between the developing brain, emotional experiences and attachment.

Dr Siegel's resources and videos on “Connection before Correction” and the “Hand model of the brain” are extremely valuable video resources explaining complex neuroscience terms in easily understandable ways, and in ways that are easily applicable to parents in supporting their children when dysregulated. Why do I love it? I love recommending Dan Siegel’s approach to emotional literacy to all parents who seek help in how to better support their children who experience dysregulation. Dan Siegal’s books and resources help parents gain a better understanding of helpful ways to respond to a dysregulated child. He stresses the importance of empathy and feeling more connected with their child through teaching effective co-regulation skills. What is a key takeaway? Connection before correction may seem like just 3 words, but it encapsulates a whole lot more than just what those 3 words mean. By helping parents understand the importance of increased connection and understanding of their children’s needs/barriers, we can also help them explore and develop their emotional literacy. This then helps create more meaningful and positive relationships between parents and children, and more open communication and emotional expression between children and parents. Why my clients should read it? All parents can benefit from increasing their understanding of their emotional experiences, common triggers of these, and also what can be done to help manage certain emotions. You can purchase "The Whole Brain Child" here: https://www.bookdepository.com/Whole-Brain-Child-Daniel-J-Siegel/9780553386691 Learn more about Dr Dan Siegel's work here: https://drdansiegel.com/ We can all agree that the ‘school world’ children live in today is completely different to ours ‘back in the day’. There are notable differences in the subjects studied, classroom layout (assigned desks vs flexible learning spaces), interests (outdoor cricket vs Minecraft), jargon used (“the bomb” vs “lit”), technology available and teaching methods provided to students (blackboards and paper vs interactive whiteboards and iPads). Consistent with these changes, there has been a shift in the way we think about and assess children’s progress, thinking and learning in school settings. Imagine that you have a son named ‘Johnny’ in Grade One. He is a vivacious and affectionate boy who loves sports and enjoys going to school. His teacher has completed her usual assessments to determine Johnny’s progress in fundamental subjects (reading, writing and maths). From Johnny’s previous school reports, you’re concerned that he’s performing below standard and don’t want him to fall behind further. One day, Johnny’s teacher and Assistant Principal sit you down and ask you to sign a consent form as they believe that given Johnny’s difficulties he may benefit from a Cognitive assessment and/or Oral Language assessment. At this point you’re thinking, my son would benefit from what? Why? How is this going to help him? The ‘What’. What are they talking about? First off, let’s define cognition. Cognition is our mental process of not only acquiring information, but making sense of it. Do these assessments have a name or is it just ‘cognitive assessment’? The most commonly used cognitive assessments in Victorian schools are:

For children in Years 11 and 12 there is the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS-IV) for individuals aged 16.0 to 90 years 11 months. However, it is rare that cognitive assessments at this age are administered for educational purposes. Cognitive assessments (or intelligence tests/IQ tests) are used in school settings to assess a child’s level of overall cognitive (aka mental) ability, learning capacity and identify their cognitive strengths and weaknesses (for example, does your child thrive with visual information? Are they good at problem solving? Do they better deal with verbal information?). What do these assessments measure?These assessments measure cognitive abilities within 5 primary indexes, or ‘areas’ of intelligence:

There are many other ‘ancillary’ or ‘other’ indexes that can also be calculated, however it’s not a ‘need to know’ for now. If relevant to your child’s case the Psychologist can explain it to you. The assessment within a whole processThe cognitive assessment itself is actually NOT the only thing Psychologists do when they conduct a cognitive assessment. Here is a brief dot point summary of the process:

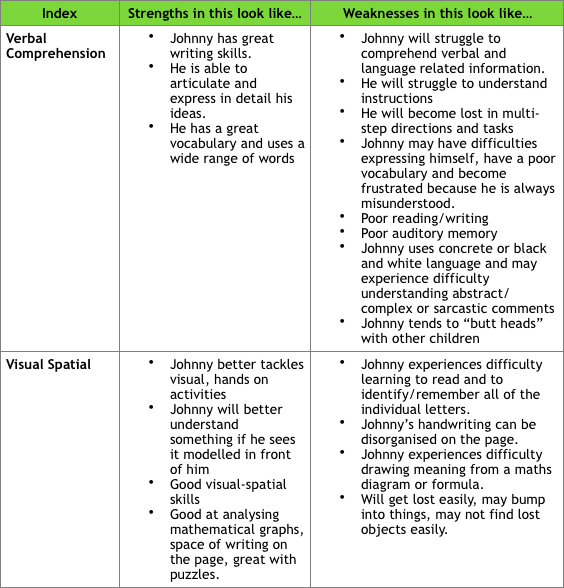

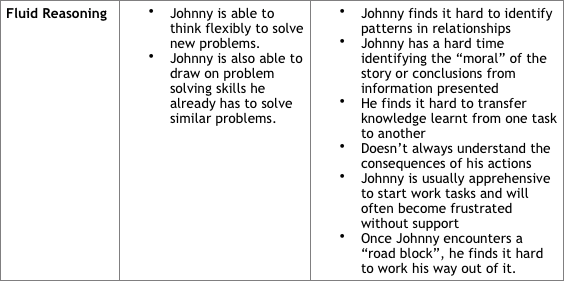

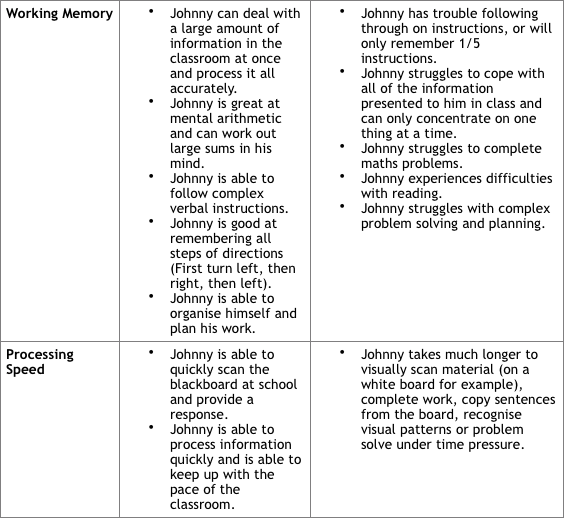

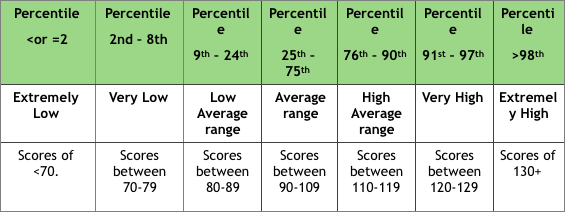

Now, depending on the unique situation of your child, there may be other things that occur alongside this ‘standard process’. For example, if you’re looking to obtain funding through the school system for Intellectual Disability, a Psychologist would have to complete other assessments AS WELL as this and write a separate funding report. Cognitive assessment, part of a formulaIt is quite often that the entire cognitive assessment process (from parent consult onwards) is paired with other standardised assessment for different referral questions. Here is a brief snapshot. Intellectual Disability: Cognitive Assessment + Adaptive Functioning Assessment Language Disorder: Cognitive Assessment + Language Assessment Specific Learning Disorder: Cognitive Assessment + Achievement Assessment (sometimes memory assessment and phonological awareness testing is also included) Giftedness: Cognitive Assessment + Gifted Rating Scales or other information gathering The ‘does this ring a bell?’ gameA good way to understand the abilities that cognitive assessments measure is to know what the “strengths and weaknesses” in these skills actually look like in school aged children. Have a look at this table and see if any of these ‘ring a bell’ or ‘ring true’ to your child. Now that we understand what it measures, how do I make sense of these results?A lot of scores come out of cognitive assessments, however I feel that parents should be knowledgeable of two things: Percentile Ranks Percentile ranks reflects how a child performed compared to children the same age. Let’s say we lined up 100 boys the same age as Johnny in order of ‘ability. The little boy sitting at position 1 would be the worst performing and 100 the best. If I told you that Johnny was sitting at the 50th percentile, it means that he is RIGHT in the middle and performing as he should be for his age OR that he is performing better than 50% of children his age. With cognitive assessments, the Average Range falls within the 25th to the 75th percentile. Standard Scores Put simply, standard scores are these converted scores that Psychologists use to determine where Johnny’s cognitive abilities lie in comparison to other children his age and what range of ability he falls under. You’ll see ranges associated with standard scores for the indexes and Full-Scale IQ. As an example, any standard score between 90 and 109 falls within the Average Range. Here is a general scoring guideline table for quick reference: What do schools do with cognitive assessment results?Psychologists make recommendations that teachers can use to develop a personalised learning plan for the child. These recommendations are made based on your child’s strengths and weaknesses. As a very simple example, Johnny might have a personal strength with visual-spatial skills but weaknesses in working memory. The psychologist might then recommend that all instructions provided to Johnny in the classroom be concise, clear and provided to him one at a time. The psychologist might also recommend that instructions or demonstrations in the classroom be highly visual in nature when being delivered to him or that verbal instructions are paired with visual stimuli. Depending on the reason for the referral, these results and the report might be passed onto a paediatrician or submitted as evidence for a funding application within the Victorian school system. The cognitive assessment process is a highly rewarding one. It provides educators and parents with the opportunity to better understand the learning needs of the child involved, and also to address your concerns as parents about why they are falling behind academically. At Hopscotch and Harmony, we have a team of Psychologists including myself who are highly experienced in conducting cognitive assessments and thoroughly enjoy collaborating with parents and educators to achieve the best outcomes for children. To make an appointment, please don’t hesitate to ring us on (03) 9741 5222. I have developed a “Guide to cognitive assessment: A cheat sheet” as a resource for schools and parents. This provides a brief snapshot of the content in this blog post. I hope you find it useful! Interested to know how therapy works with pre-schoolers? In child centred therapy, the child is provided with a safe and supportive environment to join with the psychologist to explore challenging issues. Children express their concerns and needs and also learn helpful ways to manage emotions in therapeutic play. What does the therapy room look like for young kids? My therapy room includes different play sites for kids. In one corner you may notice a dollhouse and human figurines. In another corner you will find a sandtray with miniature figures such as animals. There is also paper based activities, social stories, puppets and soft toys, and other toys appropriate for sensory play, constructive play and pretend play. Most play sites are based on the floor or mats and the tables and chairs are child friendly. What happens in the therapy room with young kids? There are two rules in the therapy room; we will keep each other safe and we will take care of the toys in the room. Parents are welcome to the therapy room to observe play therapy techniques and to track their child’s progress in sessions with the psychologist. Young kids are encouraged to bring their favourite toy to their initial session as a source of comfort and are free to explore the play room with curiosity and openness. In the therapy room, young kids will have the opportunity to learn about emotion expression and regulation, turn-taking and problem solving with play! Parent participation in session and between sessions is always encouraged. Mindful parenting strategies relating to the treatment goals can also be discussed and practiced in sessions. What other sources of information can be helpful in the early stages of therapy? Parents can bring copies of health professional reports or letters from educators to the initial parent appointment. It is valuable for the psychologist to gather information about the child’s developmental, medical and family history. The psychologist may also conduct a kinder observation to refine the treatment goal after initial information is collected with signed consent by the parent. What are some reasons why parents may consider to make an appointment with a psychologist for their young child?

Who can I speak to so I can ask for a referral for my young child? No referral is needed to see a psychologist. Please keep in mind that if you are interested in a service with Medicare rebates you will need to provide a signed referral letter from a paediatrician or G.P. Your child may be eligible for a Medicare rebate for up to 10 sessions per calendar year. Alternatively, your child can attend Hopscotch and Harmony as a private client.

Does it blow you away when you see your little one master a new skill? Are you fascinated by how your child learns?

Understanding a little about cognitive development gives you an insight into how little minds work. Cognitive development refers to the process of growth and change in intellectual abilities such as how a person perceives, thinks, and gains understanding of his or her world. By learning what is typical and appropriate for general age groups, behaviour can be considered in the context of a child’s cognitive development. You might learn behaviour that’s bothering you is a typical part of development and this knowledge may ease any accompanying frustration you feel. You might even feel relieved knowing you don’t need to try to change your child. You don’t have a ‘naughty’ child nor are you a ‘bad’ parent. Piaget (1936) was an influential psychologist and his theory of cognitive development continues to shape our understanding of child development. His four proposed stages are outlined below: Sensorimotor Stage From birth until about 2 years, infants are busy discovering relationships between their bodies and the environment. The child relies on their senses of seeing, touching, sucking and feeling to learn. Object permanence is an important part of this stage. If you cover a toy with a blanket and your baby stops showing interest then it is likely that he hasn’t mastered object permanence yet. He thinks that the object doesn’t exist anymore as it cannot be seen. If your baby actively looks for the toy under the blanket then you can be confident that your little one understands that the toy still exists even though it can’t be seen. Babies also learn through trial-and-error and cause-and-effect multiple times a day. It might be that he shakes a rattle to make noise or pulls a string to bring a toy closer to himself. Babies are little scientists and quickly learn to solve problems, and make predictions about how their behaviour has an effect on others. They way you respond has an impact on the conclusions infants will make. Preoperational Stage Have you noticed that your 2-year-old calls all ladies ‘mummy’? Or all men ‘daddy’? Welcome to the preoperational stage of development! During this stage, children react to all similar things as if they are identical. They also make inferences from one specific object to another. Looking at an orange in the fruit bowl your child is likely to reason, “My ball is round, that thing is round, so that thing must be a ball”. Children are yet to use logic to understand ideas. This is why you might be experiencing frustration trying to use logic to explain something to your preschooler. Most preoperational thinking is self-centred. I bet you’ve noticed that your child has difficulty understanding life from any other perspective than his own, right? Your child at age 4-7 is very me, myself, and I oriented. At this stage your child assumes that other people see, hear, and feel exactly the same as he does. Notice that when two children at this developmental stage are playing with one another, although they probably talk to each other in turn, they have their own agenda and may seem oblivious to the content of what the other child is saying! All normal! As children work through this stage they build on their experiences and adapt to the world around them. They become able to mentally represent events and objects, and engage in symbolic play. The Concrete Operational Stage Children in this stage are generally around 7-11 years. This is when we see children use logic to solve problems, but for the most part this logic is limited to physical objects. These children are not yet able to think abstractly or hypothetically. You will find your child has lost their “all about me” thinking as well. One indication that a child has reached this stage is that they understand something stays the same quantity even though its appearance changes. This is called conservation. For example, if liquid is poured from a short wide container into a tall narrow container your 8-year-old will likely tell you it’s the same quantity of water. Your 5 year-old, on the other hand, is likely to insist that there is more water in the taller container because the appearance has changed. The Formal Operational Stage This final stage in Piaget’s theory begins at about 11 years of age and continues throughout adulthood. Piaget did indicate, and this is supported by subsequent research, that some people never reach this stage of cognitive development. This stage sees adolescents gain the ability to think in an abstract manner. Ideas (such as maths problems) can be manipulated in your child’s head without having to rely on physical objects. How a child solves the following problem gives an indication of whether or not they have reached the formal operation stage of development: If Sam swims faster than James and Declan swims faster than Sam, who is the fastest swimmer? Children in the Concrete Operational stage might need to draw a picture to help them solve the problem, whereas children in the Formal Operational stage can reason the answer in their heads. In the early years of life, relationships with primary caregivers provide the experience that shapes how genes express themselves within the brain. Piaget’s take home message was that children need to be active in exploring the world around them and making discoveries. Opportunities are everywhere! So encourage your child to learn through experience and observe the beauty that is a child learning and developing. Caring, responsive adults play a vital role in providing stimulation and support for children’s cognitive development. |

Categories

All

|

Hopscotch & HarmonyAt Hopscotch & Harmony Psychology, you can expect compassionate care and evidence-based guidance on your journey to wellness.

With clinics in Werribee and Belmont, as well as providing online counselling to clients who live throughout Australia, our dedicated team of psychologists and dietitians are committed to providing support to children, teenagers and adults. With a focus on understanding your unique needs, we offer tailored solutions to foster growth and resilience. Trust in our experience and dedication as we work together towards your well-being. Welcome to a place where healing begins and possibilities abound. |

Our services |

Contact usHopscotch & Harmony

Child, Teen and Adult Psychology Our Locations:

WERRIBEE: 1/167-179 Shaws Rd

BELMONT: 92 Roslyn Rd AUSTRALIA-WIDE: Online counselling |

Hopscotch and Harmony respectfully recognise the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people as the first Peoples of the continent now called Australia.

We acknowledge the Bunurong and Wadawurrung people of the Kulin Nation, the traditional owners of the land on which we work, and pay our respects to their Elders, past, present and emerging.

© 2024 Hopscotch and Harmony Pty Ltd

RSS Feed

RSS Feed