|

When looking at the research, different studies, together with anecdotal evidence, there are various results in ratios between males and females identified as autistic, ranging from 2:1 to 16:1, respectively! So why are there such differences across studies? There are several possible reasons for this, some of them being:

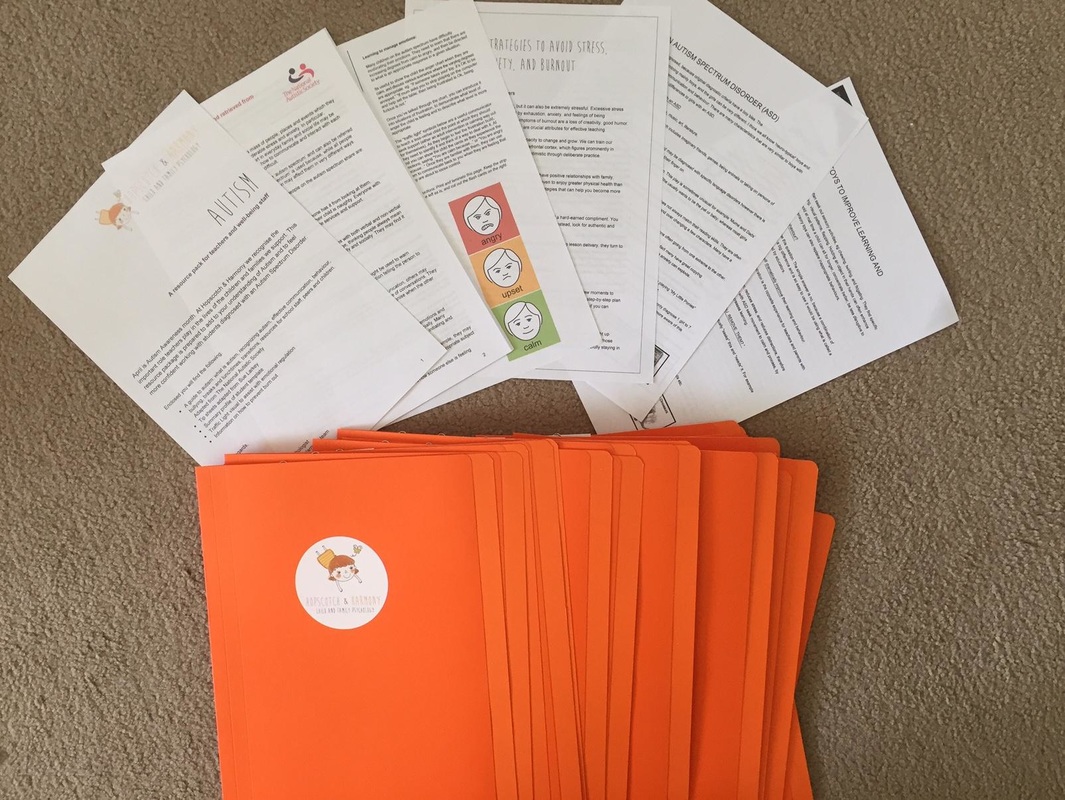

The below table illustrates the differences between more obvious characteristics of Autism compared to more subtle characteristics (National Autistic Society): Often, I hear parents say that their daughter’s teachers don’t notice any ‘problem’ in the classroom, and in fact, they’re considered the perfect student! This is often quite distressing for parents as their child may to experience intense emotional outbursts the moment they arrive home. Girls tend to mask their behaviours quite well, as they are more motivated to engage socially. They spend excessive amounts of energy doing so at school, as to not get noticed and fly under the radar. Because of this mental and emotional exhaustion, here comes the meltdowns when they finally feel like they can be ‘themselves’. The expressive language used by autistic females is often exceptionally good, which can then mask their difficulties processing verbal information. Their eye contact might also be quite good, they may do ‘small talk’ well and can be very chatty, though these tend to be quite exhausting and when their energy is not replenished, can cause significant distress and other mental health conditions over time. Females who seek therapy present with mental health issues such as eating disorders, personality disorders, depression, anxiety and self-harming behaviours that can divert the clinician’s attention away identifying these individuals as autistic. Mothers who identify with having autistic characteristics are typically the ones who bring their young daughters into therapy or for assessment, as they notice the difficulties in their child as similar to their own difficulties, and don’t want their child to go through the same challenges as they did growing up. Our mission at Hopscotch and Harmony is to smash the stigma of mental health conditions and a big part of our work is working with young children, teens and adults who are autistic. There is so much support out there and this will continue to grow as our understanding of autistic needs deepens. Listening to so many autistic individuals talk about their relief and enhancement of self-understanding when the assessment process identifies them as autistic are some of the benefits of going through the formal assessment process. Though this is not true for everyone. Some people identify with having autistic characteristics or self-diagnose as being autistic, and are content with being aware of their strength and struggles, and don’t want a formal assessment. Some people may overly-identify with a diagnosis and feel like ‘something is wrong with them’. This is where clinical judgement and parental intuition come into play… there is never a black and white answer, is there? Many psychologists at Hopscotch and Harmony are highly skilled in the autism assessment process. If you want more information on this process, please complete our assessment booking enquiry form FOUND HERE When speaking to the parent of an Autistic child, it's important to be mindful and respectful of their experiences and feelings. Here are some things you should never say to the parent of an Autistic child:

Instead, focus on offering your support and understanding. Ask the parent how you can help or what they need, and listen without judgement. Let them know that you are there for them and that you care about their child. By showing empathy and understanding, you can help create a warm and supportive environment for the parent and their Autistic child.

Why should we know the difference?A common theme that comes up in working with children and adolescents is bullying. Often I hear reports from clients who feel they are being bullied at school, which is obviously troubling for both the client and the parent, as nobody wants to be bullied and no parent wants to hear that their child is being bullied, or feels uncomfortable going to school. Although a child may genuinely believe that they are being bullied, not all reports of bullying can actually be defined as such. In some cases the child may perceive teasing to be bullying, whether it is intended to be playful and harmless or goes too far and becomes hurtful. In particular, some children may tend to have a more challenging time interpreting social situations and may perceive teasing as bullying. Therefore it is important that all kids and their parents understand the difference so that they can appropriately handle the situation, whether that be to work with the school to address the bullying and/or to seek assistance through school programs, a psychologist or counsellor to help develop and build a child’s resilience and assertive communication skills. What is bullying and teasing?Bullying: The National Centre Against Bullying (NCAB) define it as when an individual or a group of people with more power, repeatedly and intentionally cause hurt or harm to another person or group of people who feel helpless to respond. Therefore bullying is not a single episode of rejection, acts of nastiness or mutual arguments, disagreements or fights. Teasing: Teasing is a social exchange and can be friendly, neutral or negative. Teasing or being mean is different to bullying as there is usually no power imbalance. Although teasing can be hurtful and unkind it’s common among children and so it is important to know the difference as they may require different responses. Whilst I understand it’s common amongst children, I don’t condone bullying or being mean, and feel that it’s important for us to have common terminology so that we can assist children in the most appropriate way. What is behaviour? Behaviour is the way someone acts or conducts themself, especially toward or around others. When discussing children’s behaviours, we often find ourselves using the terms positive and negative behaviour or appropriate and inappropriate behaviour. Difficult Behaviours and why we act so quickly around them Children may at times display negative or inappropriate behaviour. As parents and adults, our first thought is to react to this behaviour straight away to try to cease it, because it is not considered appropriate in the current situation. The behaviour may be having negative effects on other people or their thoughts about the child or about us! Why do behaviours occur? Behaviour occurs for many reasons. The reasons we behave are called functions. There is often a function of every behaviour we see or do. The function is the Why. A person may be trying to gain someone’s attention, seek control of a situation or express their thoughts or feelings, none if which are wrong. The difficulty some children may encounter is in understanding how to use positive and appropriate behaviours instead. Noticing why behaviour is occurring is extremely important. We need to know why behaviour is happening and what a child wants, so that we can assist them to gain this in an appropriate way. When children have not independently clued onto how to behave in a positive manner, to get what they are after, they may continue to use negative behaviour because this is what they are familiar with… and maybe it has been working for them so far! Proactive and Reactive Methods Reacting to behaviour to try to stop or reduce behaviour after it has occurred is surprisingly called… a reactive strategy. Reactive strategies can include giving verbal feedback to a child or a fair and logical consequence occurring. Teaching a child a skill (like how to gain something in an appropriate way) before the child is in a situation is called using a proactive method. Using a proactive strategy gives a child the appropriate behaviour to use, and gives them the best chance to demonstrate a positive behaviour. They then have a better chance of what they want, which will encourage them to use the desired behaviour again. Do we need a more systematic game plan? If you find that a negative behavour is occurring again and again, and you can’t seem to redirect the behaviour to something more appropriate, these tips may help:

- Do they want someone’s attention? - Do they want to be in the ‘drivers seat’ of the situation? - Are they trying to communicate a thought or a feeling? - Are they trying to release frustration? - Are they trying to regulate themselves or self-soothe? - Are they trying to avoid something?

Knowing how to respond to behaviour, to encourage positive skills, and discourage negative behaviour is a tricky task. Every child is extremely different and will be encouraged and discouraged with varying methods of adult responses. If you have noticed difficult behaviours and would like some assistance to increase your child’s skills and to encourage positive behaviours, please contact us - we are here to help. What is Autism Spectrum Disorder? Autism Spectrum Disorder is characterised by difficulties in the core areas of social communication and language, together with restricted, repetitive behaviours, interests, or activities. The presentation of Autism Spectrum Disorder varies considerably between individuals. Therefore, a comprehensive assessment is needed. Who Makes a Diagnosis? In Victoria, best practice for an Autism Spectrum Disorder Assessment involves a multidisciplinary team. This means that multiple professionals work together to carry out a wide-range of assessments. A multidisciplinary team usually includes: a paediatrician or child psychiatrist, a psychologist, and a speech pathologist. In addition, other professionals might also be included, such as an occupational therapist. All professionals come together to bring insight based on their areas of expertise. What might be involved in a comprehensive Autism Spectrum Disorder Assessment? An Autism Spectrum Disorder Assessment involves an in-depth analysis of your child’s developmental and medical history, as well as an assessment of your child’s current strengths and challenges. Each professional gathers this information over multiple sessions. Generally, they will do this through:

Once each of the professionals has completed their assessment report, the paediatrician or child psychiatrist will bring all the results together and make the final decision as to whether the criteria for Autism Spectrum Disorder is met. Where do I start? If you would like to discuss your situation and the possibility of Autism Spectrum Disorder, please book in an appointment with one of our psychologists experienced in the assessment and diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder. Alternatively if you are sure you would like an assessment you can make an appointment to see your G.P. and request a referral to see a paediatrician. The paediatrician will do an initial assessment of your concerns and may then refer you to a psychologist and a speech pathologist for a multi-disciplinary ASD assessment. When might these occur?Autistic children are most commonly thought of when there is mention of sensory sensitivities or sensory behaviours. One of the criteria that a child with Autism may meet is experiencing hyper (high) or hypo (low) reactivity to sensory input or unusual interests in sensory aspects of the environment. There are also children who may not have a diagnosis who may present with sensitivities to some extent. How do I know what to look for?There are many categories of senses: sight, sound, touch, taste, smell, balance and we can even extend to include proprioceptive and vestibular input. There are two common presentations of sensory sensitivities. Hypersensitivity occurs when sensory input exceeds a person’s ability to cope. This is a low sensory threshold and the child is explained as a sensory avoider. Hyposensitivity occurs when greater than normal levels of input are required for registration. This is a high sensory threshold and the child may be seen as a sensory seeker. Why might a child engage in sensory seeking or sensory avoiding?Whether a child is seeking or avoiding sensory input, there are reasons behind the behaviours we can see. These may include the following, but can include many more:

What can I do to help?As with any behaviour, if we can find out or make a prediction of why it is happening and what function it serves, we have a much better chance of making a successful support plan for the child. But how do you figure this out? Watch your child in various environments and observe their behaviours and reactions or even just ask them. Ask others involved in your child’s care also – it’s important to gather information. Be a detective! Here are some tips that were shared on our blog recently about functions of behaviour – check it out: https://www.hopscotchandharmony.com.au/blog/behaviour-the-importance-of-figuring-out-why. Below are some common examples of behaviours and how you may be able to assist. If a child is seeking sensory enjoyment: Yes, sometimes these behaviours are enjoyable for a child, but are disruptive to the child’s opportunities to socialise or it may be impacting/disrupting their learning or attention. If this is a behaviour that is safe, gently speak to your child (or use pictures) to explain it is not time for this just now; however, they may have some time to engage later. Remember, it’s okay for a child to engage in these behaviours sometimes; they serve a function. You also may like to suggest to a child they engage in these when it is time for them to follow their own ideas/explore their environment or when they take a break. If a child is engaging in a disruptive sensory seeking behaviour: If you believe the behaviour is inappropriate or disruptive, For example, if a child enjoys biting and sucking their school T-shirt, but this is the tenth one you’ve purchased this year! you may like to further explore why are they biting that material in the first place (Boredom? Anxiety? Is it a concentration aid? Does it calm them?). You may then consider providing alternative opportunities that serve the same function. If this really is just for comfort or concentration, they may like to have a more appropriate option (a small piece of similar material available to them that they can use). If this is due to anxiety, we need to look further into teaching effective and appropriate coping skills. Your child needs a proactive strategy. If a child is a sensory avoider, provide appropriate ways for sensory avoiding where possible: Can you help the child to communicate their discomfort in an appropriate way? Or maybe a child can be taught how to minimize the effect the sensory experience has on them. They should always be taught how to cope through a sensory experience as well as being given a way to minimize its effects. The world is an unpredictable place and your child may inevitably experience what they are trying to avoid at some stage. A summary - How do we understand and how do we help?

If you believe your child may benefit from an integrated and individualised plan, contact us and our team will help you with your next step. “It will never rain roses: when we want to have more roses, we must plant more roses”. ― George Eliot (Novelist, poet, journalist, and one of the leading writers of the Victorian era) This simple 5 minute clip is a great introduction to autism! With an aim to raise awareness amongst those who don't really understand the condition, this short film is a good place to start.

Who might benefit from watching?

Putting our ASD Teacher Resource Packs together! Putting our ASD Teacher Resource Packs together! April is Autism Awareness month. This year we want to reach out and help teachers understand more about autism and to feel confident in supporting children who have autism. For this reason we have created Autism Spectrum Disorder Teacher Resource Packs especially for the classroom teachers and school well-being staff of our clients. This month our psychologists are handing these resource packs out to the parents of each child on the autism spectrum to pass on to their school. The packs contain the following:

In Term 1 we ran our first Lego Social Skills Group. We had 10 participants from ages 5-13 across two sessions. The children quickly warmed up and became engaged and enthusiastic to belong to the group. The group members had a diverse set of interests, skills and personalities, and we enjoyed getting to know them all. Parents generally enrolled their children because they felt a need for the children to learn more effective social skills and that meant different things for different families. For some children this meant learning assertiveness or knowing how to make and keep friends. For others, the parents were concerned about limited cooperation, sharing and turn-taking skills. While many of the children had a diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder and/or Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), this was not a criteria for group entry. The one thing all children had in common was their love of Lego and eagerness to work on the group projects. We started each session with a mini-lesson. These lessons included topics such as: tone of voice, assertiveness, communicating with our eyes, and how to fill someone's 'bucket' with our kind words and actions. In groups of three, children then began their group Lego projects. One child was the engineer (in charge of reading the instructions), one child was the supplier (had to find the pieces) and one child was the builder (put the pieces together). These roles changed each week. The children had to communicate clearly, wait their turn, practice frustration tolerance, and do their job in order for the project to be successful. They also got to celebrate together and felt a joint sense of pride when they achieved their goal. The role of the psychologists was to facilitate the interactions and assist the children with problem solving, task behaviour, joint attention, effective communication and adaptive coping strategies when things weren't going their way, and provided positive reinforcement for appropriate social interactions. The content of our group sessions was guided by research that has shown Lego-based interactive therapy in this format improves social competence over the long-term. In the final weeks of term, we taught the children how to make stop motion animations using the Lego Movie Maker app. Children worked in pairs to decide on characters, build a set, create a plot and take the photos to make their movie. Again, the psychologists coached the children to use their social communication skills during this project. All in all, Lego group was a hit, and the children enjoyed the sessions (and I suspect for the most part they did not even realise they were 'learning' as the coaching merged seamlessly into the activities).

Bring on Term 2! To register click here  Today Sesame Street introduced us to Elmo's friend Julia, who has autism. Julia is part of the Sesame Street and Autism: See Amazing in All Children initiative. This initiative aims to increase understanding of autism and to reduce stigma and isolation often experienced by children with autism and their families. The unique quality and talents of all children are celebrated and the commonalities that children with autism share with all children are emphasised. There are excellent resources available on the Sesame Street website for families and carers of young children to assist with the challenges of daily living. What you will discover:

If you want to learn more about Autism Spectrum Disorder but don’t know where to start then here is a selection of our favourite books and resources to get you going. Parent Education: Ten Things Every Child with Autism Wishes You Knew: Updated and Expanded Edition (by Ellen Notbohm) Recommended for parents who have a child recently diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder. The Complete Guide to Asperger's Syndrome (by Tony Attwood) A comprehensive volume written in easy-to-read non-technical language. There is a good mix of research information, first person reports and clinical information. Managing Meltdowns: Using the S.C.A.R.E.D. Calming Technique with Children and Adults with Autism (by Will Richards) This brief book is useful for parents and teachers to determine the cause of meltdowns and how best to avoid them. No More Meltdowns (by Dr Jed Baker) Great information and strategies for home and school. Three sections: The Problem, The Solution and Plans are interwoven with stories of how the strategies have been used with different children. Books for Children: The Red Beast: Controlling Anger in Children with Asperger's Syndrome (by K.I. Al-Ghani) This storybook is written for children aged 5+, and is an accessible, fun way to talk about anger, with useful tips about how to 'tame the red beast' and guidance for parents on how anger affects children with Asperger's Syndrome. The Panicosaurus: Managing Anxiety in Children Including Those with Asperger Syndrome (by K. I. Al-Ghani) This fun, easy-to-read and fully illustrated storybook will inspire children who experience anxiety, and encourage them to banish their own Panicosauruses with help from Mabel's strategies. The helpful introduction explains anxiety in children, and there is a list of techniques for lessening anxiety at the end of the book. Why Do I Have To?: A Book for Children Who Find Themselves Frustrated by Everyday Rules (by Laurie Leventhal-Belfer) This is the ideal book for children who have difficulty coping with the expectations of daily living, as well as for their parents and the professionals who work with them. The Asperkids Secret Book of Social Rules (by Jennifer Cook O’Toole) The handbook written by a mum with Asperger's Syndrome says it's a book "that every adult Aspie wishes they’d had growing up". Ideal for 10-17 year olds. Can I Tell You About Asperger Syndrome?: A Guide for Friends and Family (by Jude Welton) Adam helps children understand the difficulties faced by a child with Asperger's Syndrome (AS); he tells them what AS is, what it feels like to have AS and how they can help children with AS by understanding their differences and appreciating their many talents. Ideal for 7-15 year olds and also serves as a good starting point for family and classroom discussions. Teaching Resources: Teacher Assistants Big Red Book of Ideas (by Sue Larkey & Anna Tullemans) Hundreds of ideas to try. Setting up the classroom, the role of the teacher assistant, behaviour in the classroom and playground, stages of anxiety, transition, sensory toys and activities. http://www.suelarkey.com.au/shopping/pgm-more_information.php?id=4 Teacher Assistants Big Blue Book of Ideas (by Sue Larkey & Anna Tullemans) Strategies regarding Social skills: playgrounds, friendships, building self esteem, bullying. In the classroom: getting on task, adapting tasks and exams, building independence. Managing anxiety and behaviour. http://www.suelarkey.com.au/shopping/pgm-more_information.php?id=78 Sensory Toys: Available from: http://www.senseabilities.com.au/ http://www.specialneedstoys.com.au http://www.suelarkey.com.au/Sensory_Shop.php  It’s not long until school starts and it’s an exciting yet anxious time for new students and families. However, when a child has ASD, commencing school can involve extra challenges and may be a source of considerable stress and anxiety for parents and child. The best way to deal with anxiety is preparation. The following tips will help prepare a child with ASD for commencing school, and make the transition easier. Create a transition book Use photos and simple language to create a book about school for your child. You can include:

Communicate with the school

Establish Routines

School visits

Anticipate problems

REGISTER FOR OUR JAN 2016 SCHOOL TRANSITION GROUP HERE! Good luck and I hope that the transition to school is a positive experience for you and your child! |

Categories

All

|

Hopscotch & HarmonyAt Hopscotch & Harmony Psychology, you can expect compassionate care and evidence-based guidance on your journey to wellness.

With clinics in Werribee and Belmont, as well as providing online counselling to clients who live throughout Australia, our dedicated team of psychologists and dietitians are committed to providing support to children, teenagers and adults. With a focus on understanding your unique needs, we offer tailored solutions to foster growth and resilience. Trust in our experience and dedication as we work together towards your well-being. Welcome to a place where healing begins and possibilities abound. |

Our services |

Contact usHopscotch & Harmony

Child, Teen and Adult Psychology Our Locations:

WERRIBEE: 1/167-179 Shaws Rd

BELMONT: 92 Roslyn Rd AUSTRALIA-WIDE: Online counselling |

Hopscotch and Harmony respectfully recognise the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people as the first Peoples of the continent now called Australia.

We acknowledge the Bunurong and Wadawurrung people of the Kulin Nation, the traditional owners of the land on which we work, and pay our respects to their Elders, past, present and emerging.

© 2024 Hopscotch and Harmony Pty Ltd

RSS Feed

RSS Feed