|

A life without worry is a dangerous thing. It would mean a lack of concern for consequences of our actions, a reduction in reflective thinking and a reduced drive to get things done by a deadline. It would mean we would step out in front of the busy road, or test if the iron is hot by using our finger. Worry has been a safety mechanism for us throughout the evolutionary process, and has help ensure our survival. The point being, that a little bit of worry is a good thing. The other end of the scale is a debilitating experience when we cannot think of anything but mistakes we have made or have a fear of the future that is enough to make us physically sick and interrupt our lives. So how do we know when to worry about worry? How much is enough? And how to help foster a sense of safety without taking away our children’s ability to experience worry and instead learn to cope with it? If compared to other children you see that your child gets worried more often, and more intensely than others, and things have persisted for some time, then it might be time to get some professional support. Other signs to look out for include irritability, avoidance of things they might have previously enjoyed, physical complaints like a sore tummy, or comments like things being ‘boring’ or ‘stupid’, when they may in fact be difficult and your child is feeling afraid. Not wanting to go to school or see friends can be a red flag for a child experiencing anxiety. As a parent, there are some things you can do at home to help foster a sense of resilience to things that may be worrying and help your child cope with those feelings. Some possible ways include:

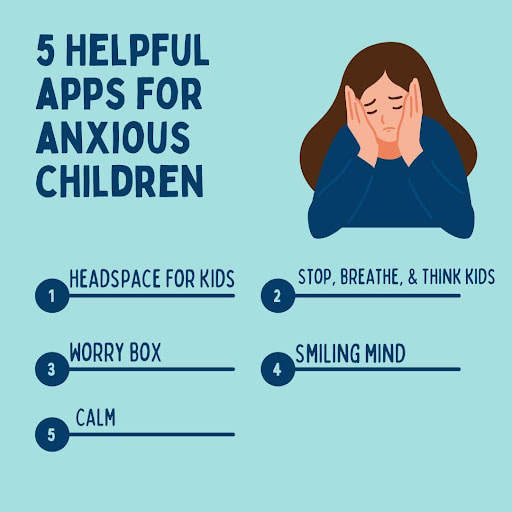

The relationship building that you do with your child will ultimately underpin these strategies. Being able to give them the confidence to believe what you say, to confide in you, and to give them the feeling of independence and competence to take on the world. Don’t minimise the positive interactions that you have together in the big jigsaw puzzle of your child’s world. Plant the seeds of the relationship when they are 5, so they know when they are 15, that you are cheering them on. While some level of anxiety is normal in children, excessive anxiety can interfere with a child’s daily activities or quality of life. There are several apps available that can help children manage their anxiety. It can provide children with tools and strategies to help them identify, challenge, and reframe negative thoughts, as well as develop emotional intelligence and mindfulness. Here are 5 helpful apps to help support an anxious child: 1. Headspace for Kids: Headspace is a popular mindfulness app that offers a special section for kids. This app provides a range of guided meditations, breathing exercises, and visualizations that are designed to help children manage their anxiety and stress. 2. Stop, Breathe & Think Kids: This app uses fun and engaging activities to help children develop emotional intelligence and mindfulness. It includes a range of guided meditations, breathing exercises, and mindful activities that can help children manage anxiety and improve their overall well-being. 3. Worry Box: Worry Box is a cognitive-behavioural therapy app designed to help children cope with worry and anxiety. The app offers a range of tools and strategies to help children identify, challenge, and reframe negative thoughts. 4. Smiling Mind: Smiling Mind is a mindfulness app designed specifically for children and adolescents. The app offers guided meditations and mindfulness exercises that are tailored to the age and developmental stage of the user. 5. Calm. This app is a popular meditation and relaxation app that offers a range of guided meditations and breathing exercises that can help children manage anxiety and stress. The app also offers sleep stories and other relaxation techniques that can help children calm down and relax before bed. It is important to note that while these apps can be helpful, they should not be used as a replacement for professional help. If a child’s anxiety is severe or interferes with daily activities, it is important to seek professional support from a mental health professional. Fear, anxiety, and stress are all related emotional and psychological responses to perceived threats or challenges, but there are important differences between them. Fear is a natural and immediate emotional response to a real or perceived threat. It is a normal response to danger and is often accompanied by physical sensations, such as increased heart rate, rapid breathing, and sweating. For example, if you hear a loud noise in the middle of the night, you may feel fear because you perceive a potential threat. Anxiety, on the other hand, is a more diffuse and generalised emotional response to perceived threats or challenges. It often involves a sense of uncertainty or apprehension about future events or situations. Anxiety can be triggered by a wide range of stimuli, and it may manifest as physical symptoms such as restlessness, fatigue, or muscle tension. Stress is a physiological and psychological response to challenging or demanding situations. It is a normal response to situations that require increased effort, such as work deadlines or public speaking. However, chronic or prolonged stress can have a negative effect on physical and mental health. PERCEIVED THREAT OR CHALLENGE Fear = Immediate response to actual or perceived danger. ⬇️ Anxiety = Diffuse and general feeling of unease or apprehension ⬇️ Stress = Physiological and psychological response to demands or pressures In summary, understanding the differences between fear, anxiety, and stress can help individuals more effectively recognize and develop strategies to manage and cope with each one. Additionally, by recognising the signs and symptoms of these responses, individuals can seek appropriate treatment or support when necessary. Overall, understanding the differences between fear, anxiety, and stress is an important step in promoting emotional and psychological well-being. Kara Vermaak. Provisional Psychologist We all have thoughts, that’s part of what makes us human. Sometimes these thoughts are pleasant and helpful, but sometimes they’re unhelpful and unpleasant. Our natural response may be to want to get rid of those unhelpful thoughts as soon as we can. Why would we choose to feel pain and discomfort? Unfortunately, trying to control these thoughts often has the opposite effect. They just keep coming back. Imagine you’re throwing a party. Everyone is having a great time, but there’s this one unwelcome, uninvited and somewhat obnoxious person who shows up at your house. You’ve decided to take charge, and show them out the door. But despite your best efforts to get rid of them, they keep finding a way back into your house. You become increasingly agitated as you see them annoying your guests, but they just won’t stay away. You soon realise that trying to get rid of them is futile. So what could you do instead? 1. Recognize the guest: Just like you would recognize the unwelcome party guest, recognise the unhelpful thought without judgment. Acknowledge that it's there and that it's causing you discomfort or distress. 2. Accept the guest's presence: Rather than trying to force the guest out, accept that they're there for now. Recognize that, just like the guest at the party, the unhelpful thought may stick around for a while, even if you don't want it to. 3. Observe the guest without judgment: Instead of getting caught up in the guest's behaviour, observe them without judgement. Notice what they're doing and saying, but focus on what you’re doing instead. 4. Let the guest be: Just like you might let the unwelcome party guest be, let the unhelpful thought be. Don't try to change it or control it, just observe it and let it exist without getting caught up in it. Eventually, you find that you’re so busy having fun, that you’ve forgotten all about the unwelcome guest, and your friends don’t seem too bothered by them either. After a while, they get bored, say goodbye and leave. Remember that just like an unwelcome party guest, unhelpful thoughts may arrive uninvited and unwanted, but they don’t have to define your experience. By accepting their existence and letting them be, they eventually pass by as just another thought. Book an appointment with Kara or one of our friendly psychologists

Jessica Cleary, Psychologist How did your kids go at the beginning of the new school year? If you do kinder or school drop-off you will have noticed some kids take the new challenge in their stride, whereas others have a much harder time with the transition and separation from their parents.

Maybe you found yourself with a little one who was crying and clinging and begging you not to leave. I feel for you if this was the case – it’s so hard! Or maybe your child complained of tummy-aches or headaches before leaving home. This is a common symptom of anxiety. It’s fairly common for some kids to have troubles adjusting to school. Although there is no magic solution when supporting your child through separation anxiety, here are some ideas for you: Find a friend It helps immensely when kids have a friend at school. Ask the teacher who your child seems to play with the most and introduce yourself to the parent at either drop off or pick up. Arrange a play date over at your house or a park to help nurture that relationship. Talk about it ahead of time If you know that tomorrow is likely to be another morning of tears and clingy behaviour then talk about it today when you are both feeling calm and relaxed. When children fear something, they need the opportunity to express and feel their feelings. Some of their worries or concerns may seem small or insignificant to us, but for them they are very real and should be believed and respected. It is important to acknowledge that the feeling of worry is very real for your child. After you've validated their feelings, then gently move to problem solving. Remind them of the fun parts of the day like playing with a friend or lunchtime (if this is fun for them). Remind them that after a little bit of upset they were able to enjoy the school day and they got to do new and exciting things. Let them know that you will ALWAYS come back at the end of the day to pick them up (or make sure they know the plan if there is after-school care). Team up with the teacher Work in partnership with the teacher. Experienced teachers have been through this before so are likely to have a few good ideas. If the separation anxiety doesn’t ease after a few days the teacher may be able to give your child a special job to do immediately upon getting to school. This will serve as a transition activity and is something for him to look forward to. Get to school early so the teacher can personally greet your child and take him to the activity. Don’t focus on the separation On the way to school talk about the first thing your child will do once they get in the classroom. It shifts the focus from the separation to the enjoyable activity. This helps them mentally prepare before they are physically at school. They start to visualise the inside of the classroom and can start to get used to the idea of being there. Something like this: “When you go to the reading corner, what book are you going to read first?” or “Which colouring in page will you choose when you get there – the train or the castle?”. Or if you have an arrangement with the teacher (see previous tip) you can talk about this with enthusiasm. Don’t talk about ‘school’ At home in the morning, don’t talk about ‘school’ too much. Talk about ‘reading time’ and ‘drawing’ and 'play time’. Talk about that first activity that he will be doing with the teacher (if you have one planned). The word ‘school’ may currently have a negative, anxiety provoking association for your child so minimise using that work might help if this is the case. Instead talk about the activities they will be doing at school that you know they enjoy. This makes the idea of school more concrete and less abstract. Transitional objects A special note from you kept in their pocket, or matching love hearts drawn on their hand your hand can help your child feel connected to you during time apart. Other issues Sometimes separation anxiety occurs in the context of more generalised anxiety or trauma. Maybe there is a real problem at school that is causing distress. Listen carefully to your child and do a little detective work if you sense there is more to the story. Could it be that they don't know how to ask to go to the toilet? Or they are being bullied? Do they find it hard navigating the school grounds at recess? Listen carefully and get more information from the teacher to help you work out what the underlying problem may be. When to seek professional support Often patience and using the above tips can ease separation anxiety. However, there are times when it is necessary to reach out for additional support. You may need further help if:

Finally Remember, your child isn’t trying to manipulate you in order to stay home. The feelings are real for your child and quite distressing. Although you may not always be able to prevent the separation anxiety, you can always empathise with your child and connect with them with cuddles and snuggles at the end of the day. You wouldn’t be the first parent to cry on your way to work after holding it together at school drop-off. This experience is so very stressful for parents. Look after yourself to help manage your own stress. Sleep (if you're at a a stage of parenting where that's possible!) and eat well and talk to a trusted friend who will listen and support you. Taking care of yourself and allowing yourself your own emotional release will help keep you centred and more emotionally available for your child. Many people tend to find it difficult to differentiate between fear, anxiety and stress. Although all experiences are quite normal, it is important to know the difference so you can seek the most appropriate support if necessary.

Here are a few defining features of the three experiences:

Fear and stress:

Anxiety:

There are three components that contribute to feeling anxious:

We have fear and anxiety in non life-threatening situations because of the way we interpret the situation. If you are struggling with fear, stress or anxiety and are needing some support, please contact the clinic to book in an appointment with one of our psychologists Do you know the phrase “Making a mountain out of a molehill”?

This can be all too familiar for people who experience anxiety One fleeting thought can trigger a spiral of related thoughts and worries And almost immediately what might have seemed like only a minor worry has become an overwhelming thought When you notice yourself spiralling, it can help to stop and question the thought You might want to ask yourself whether the thought is a fact, and try to find evidence to support or debunk your worry You’ll likely find that the thought is just that...a thought! If you are wanting support to manage worry or anxiety, please book an appointment with one of our friendly psychologists For some people who experience symptoms of anxiety, it can feel like an all consuming tug of war with their own internal monster.

The monster, in this instance, represents your... - anxious thoughts - your concerns - your “worst case scenarios” How physically and mentally exhausting must it be to constantly be fighting against your own thoughts? But what might happen if you drop the rope? Imagine how freeing that would feel! When you notice yourself fighting with your thoughts, acknowledge that you’re in a battle of tug of war, and choose to let go of the rope. If you are needing support to manage your anxious thoughts, please contact our clinic to book in an appointment Anxiety is one of the most common childhood disorders. Most commonly a child will experience one of the following forms of anxiety:

Some of the ways anxiety may present in your anxious child:

The good news is that anxiety can be managed through therapy to learn how to decrease those worrying thoughts, but you as a parent or caregiver can also help your anxious child by teaching them to calm down and relax their bodies and minds. One technique that you can teach to your anxious child to help them relax is Progressive Muscle Relaxation (PMR). Often when we experience worrying thoughts and events our bodies will respond with muscle tension. This tension we feel can be uncomfortable making it difficult to relax and even go to sleep at night. PMR is the process of tensing different muscle groups for a few seconds and then releasing the tension. This is done in part so that we can identify the areas that we hold the most tension and also so that we can distinguish between tension and relaxation. Here are some basics you can try to help your child using Progressive Muscle Relaxation: Preparation:

What to say: "Take some deep calming breaths in through your nose and out through your mouth... Imagine your tummy is a big balloon and when you breathe in the big balloon is filling with air, and as you breathe out, the air is slowly escaping and the balloon becomes small again. Now...squeeze your toes and feet into a tight ball... hold this... (five seconds)... now relax...let them go loose. Tighten the muscles in your legs by pointing your toes...hold the muscles tight...(wait five seconds)... now let go and feel your legs go as loose as cooked spaghetti. Let's focus on your tummy now. Tense the muscles in your tummy by squeezing it in... hold this... (wait five seconds)...now relax...notice how good your body feels. Lift your shoulders as high as you can, bringing them up to your ears...hold this... (wait five seconds)...now relax....breathe in.... and breathe out... Next you can tense your arms and hands, by stretching them forward and tightening your hands into a tight ball, like you are squeezing a lemon...hold this... (wait five seconds)...now let your arms go floppy like cooked spaghetti...notice how relaxed they feel... Let's move to your face...tense your face by scrunching up your whole face...wrinkle it up as hard as you can...hold this... (wait five seconds)...now relax. Take another deep, calming breath in through your nose and out through your mouth... When you are ready, gently open your eyes and notice how good and calm your body feels." . If you would like more support for your child, please contact one of our friendly psychologists! Tim Walker. Mental Health Clinician The Tiger Who Came to Tea is a children’s book. A young girl is surprised when a tiger enters the house at dinner time. Naturally this is an unexpected and difficult disruption! Rather than avoiding or resisting the tiger, the young girl offers it some tea. In fact, the tiger eats absolutely everything! The girl decides to accept him. The more food the tiger needs, the more she offers him. The girl and her family make room for the tiger, and finally it leaves. If we think of the tiger as anxiety knocking at the door, this story is a great example of using mindfulness and flexible thinking, individually and as a family, to manage anxiety. Whilst not based on mindfulness concepts, this story is a good analogy for sitting with anxiety in our lives, to better manage mental health. Seeing what is true, we hold what we see with kindness

Have you been feeling “off” or not like yourself? Have you struggled with feeling depressed or anxious? Have you struggled with your body image or feelings about your eating behaviours? If so, you are not alone and there are many others out there who experience similar feelings. It can be hard to deal with these difficulties alone, but you don’t have to! Getting support can be so helpful. Here are some tips to help you start to feel a bit better: 1. Notice, name and acknowledge your feelings and reactions. When we push down what we are feeling, it’s like trying to hold in a cough. Usually you hold it in and it gets stronger until it bursts out in a coughing explosion. When a feeling or reaction arises, we can say to ourselves: ‘I notice that I am feeling stressed, my body is telling me that through feeling hot and my heart racing.’ 2. Sit with that feeling without trying to make yourself feel bad about it. You can do this by saying ‘It’s been a hard day and I'm feeling upset, but that’s okay and this will pass’. Try to let the feeling wash over you. Each and every day that you try to notice your feelings and thoughts, helps you gain a better understanding of yourself. Self knowledge is so powerful in improving your mental health. Book in a session with Alayne to learn more about mindfulness and how to incorporate it into your life. **Enjoy this guest post from friend of the practice, Charlie. We came across this piece when Charlie's mother shared it in a homeschooling Facebook group. Charlie accepted our invitation for this to be published on our Hopscotch & Harmony Blog because we knew how helpful it would be to other children and parents. Thank you Charlie! Hello, I'm Charlie.

I started homeschooling at the beginning of year 6 in 2020. I will admit that sometimes when it comes to schoolwork I can behave in ways that some people might call “defiant” and “stubborn”. I want to help other families find a way to have a happy and fun time homeschooling, so I'm writing this to help other people even though I don't love writing. I'm going to talk about possible reasons for defiance now (these are from my experience and are not 100% going to apply to all children). Most of the time I don’t know what triggers me to become defiant in the first place. But later, when I can think about it I realise I was anxious. I don't always know the reason for me being anxious. But sometimes I do, for example–

So, we have looked at some things that caused me to behave in ways that some people would call “defiance”. Here are some solutions to try which I think might work. Once again these are not 100% going to accommodate every child's needs, but they helped me. .

If I can help one family homeschool more happily, this will make all this writing worth it! Thank you Charlie. You are surely familiar with the concept of separation anxiety, particularly in children. The tears and clinginess that could be experienced when a child first separates from their parents. Of course, it’s very appropriate for young children to experience some mild anxiety when they first start school or spend their first night away, though with some practice, are soon able to regulate themselves during times of separation because they know their caregiver will come back for them. Then there are children who are not able to regulate themselves and continue to show signs of distress for an extended period of time. In the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders - Fifth Edition (DSM-5, 2013), Separation Anxiety Disorder is categorised by showing developmentally inappropriate and excessive fear or anxiety concerning separation from those to whom the individual is attached for at least 4 weeks in children and adolescents (if not better explained by another condition such as refusal to leave home because of excessive resistance to change in autism spectrum disorder, amongst other conditions). In this most recent edition of the DSM-5, adults have now been included in this diagnosis, though the length of excessive fear lasts for more than 6 months. One of the major theories that inform separation anxiety is Attachment Theory, first founded by John Bowlby then extended by Mary Ainsworth. The basic perspective of Attachment Theory is that the kind of bonds we have in our early life shapes the kind of relationships we form as adults. The developing child builds up a set of models of the self and others, based on repeated patterns of interactive experience. These internal working models are thought to form relatively fixed representational models which the child uses to predict and relate to the world. A securely attached child will store an internal working model of a responsive, loving, reliable caregiver, and of a self that is worthy of love and attention and will bring these assumptions to bear on all other relationships. On the other hand, an insecurely attached child may view the world as a dangerous place in which other people are to be treated with caution, and see themselves as ineffective and unworthy of love. Within the first 6 months of life, parental responsiveness is a fundamental factor impacting the quality of attachment. This is where mirroring responses are crucial. The onset of a smiling response at 4 weeks marks the beginning of the cycles of interaction between the caregivers and their baby. The baby’s smile evokes a mirroring smile in their parent; the more they smile back the more the baby responds, and so on. These are called ‘mirroring’ responses because it is thought that what the baby sees when their caregivers copy their expressions, is in fact, themselves… i.e., they are developing their sense of self. The physical holding, protection, nurturing and caring that is also felt by the infant further creates the sense of inner security. Between 6 months and 3 years old, the goal for the child is to keep close enough to their caregiver, to use them as a secure base for exploration (i.e., separation) when the environmental threat is at a minimum, and to exhibit separation protest or signalling danger when the need arises. The over-anxious parent may inhibit the child’s exploratory behaviour, making them feel stifled or smothered; conversely, the parent that may not have the capacity to be attuned to the child’s needs may inhibit exploration by failing to provide a secure base, leading to feelings of anxiety or abandonment. Attachment relationships continue to evolve throughout the lifespan. The child-parent relationship forms the primary attachment figures until adolescence, which is when peer relationships become the primary attachment figures, then romantic relationships in adulthood. If a child has developed an early insecure attachment and an internal working model/core belief that others can’t be trusted and they are unlovable, there is a tendency for later peer and romantic relationships to reinforce and strengthen this internal working model. For example, a teenager with this internal working model may act either by avoiding developing close relationships, being ‘clingy’ or controlling of others, which would elicit undesired responses from others that will reinforce their initial core belief. How can therapy reduce or eliminate excessive separation anxiety?A key element in psychological therapy, whether that is for children, adolescents or adults is for the therapist to become a ‘safe base’ that the patient can feel secure to ‘explore’, whether that is the exploration of the physical environment for young children (play) or their internal world (adolescents and adults). Many of the elements that foster a secure early attachment as outlined in Attachment Theory are typically utilised in therapy (i.e., mirroring, being highly attuned/sensitive to the patient’s needs, support, validation, unconditional positive regard) so the patient can first start to develop a secure sense of themselves, which only after this is achieved can extend to feeling secure with significant others. Of course, as parents tend to enact their own attachment style onto their children, parenting support and explicit teaching of responses that foster a secure attachment, especially for young children is also an essential component of therapy.

by Melissa Bailey, Psychologist Anxiety is one of the most common childhood disorders. Most commonly a child will experience one of the following forms of anxiety:

Some of the ways anxiety may present in your anxious child:

The good news is that anxiety can be managed through therapy to learn how to decrease those worrying thoughts, but you as a parent or caregiver can also help your anxious child by teaching them to calm down and relax their bodies and minds. One technique that you can teach to your anxious child to help them relax is Progressive Muscle Relaxation (PMR). Often when we experience worrying thoughts and events our bodies will respond with muscle tension. This tension we feel can be uncomfortable making it difficult to relax and even go to sleep at night. PMR is the process of scrunching up different muscle groups for a few seconds and then releasing the tension. This is done in part so that we can identify the areas that we hold the most tension and also so that we can distinguish between tension and relaxation. Here are some basics you can try to help your child using Progressive Muscle Relaxation: Preparation:

What to say: "Take some deep calming breaths in through your nose and out through your mouth... Imagine your tummy is a big balloon and when you breathe in the big balloon is filling with air, and as you breathe out, the air is slowly escaping and the balloon becomes small again. Now...squeeze your toes and feet into a tight ball... hold this... (five seconds)... now relax...let them go loose. Tighten the muscles in your legs by pointing your toes...hold the muscles tight...(wait five seconds)... now let go and feel your legs go as loose as cooked spaghetti. Let's focus on your tummy now. Tense the muscles in your tummy by squeezing it in... hold this... (wait five seconds)...now relax...notice how good your body feels. Lift your shoulders as high as you can, bringing them up to your ears...hold this... (wait five seconds)...now relax....breathe in.... and breathe out... Next you can tense your arms and hands, by stretching them forward and tightening your hands into a tight ball, like you are squeezing a lemon...hold this... (wait five seconds)...now let your arms go floppy like cooked spaghetti...notice how relaxed they feel... Let's move to your face...tense your face by scrunching up your whole face...wrinkle it up as hard as you can...hold this... (wait five seconds)...now relax. Take another deep, calming breath in through your nose and out through your mouth... When you are ready, gently open your eyes and notice how good and calm your body feels." The following resources can further assist your child to relax using Progressive Muscle Relaxation:

Written by Dr Chaille Breuer, Clinical Psycholoigst Bedtime can be a time when children feel the relief of recharging their batteries for another day. It can also be a time when children are alone with their thoughts and their minds can feel really busy. Some children find themselves replaying the day that has just past, others think about what might happen tomorrow. For many, it can be a time when the darkness and noises outsides prompt their little minds to wonder about monsters and other scary things. Here are 5 simple and creative ways to manage worries at bedtime: 1. Feed worries to a worry monster Help young children to let go of their worries before they go to sleep by feeding them to a worry monster. You can create a friendly worry monster with your child by using an old tissue box. Paint or cover the tissue box with your child’s choice of colours and patterns and turn the opening into a mouth by adding some paper teeth. Once you’ve created the monster you can encourage your child to feed their written or drawn worries through its mouth (e.g., making friends at kinder, going swimming etc.). If your child struggles with writing or drawing, parents can help with the process. The monster likes to eat worries so your child can let them go from their mind. If the idea of a “friendly monster” might prompt some discomfort - you can choose your child’s favourite animal or character instead. 2. Teach your child to meditate Encourage children to learn how to relax their minds and body by teaching meditation skills at bedtime. There are many relaxation scripts written especially for children that encourage positive imagery, breathing and muscle relaxation techniques. Relaxation techniques can help calm busy minds and help get children ready for sleep. A helpful book to use is Mini Relax by Debbie Wildi (can be purchased from http://www.bookdepositry.com). Debbie’s book of calming stories helps children imagine themselves sliding on rainbows, walking through the fairy forest and see the world from a red air balloon. Each story introduces children to breathing and muscle relaxing techniques in a creative story format. Alternatively, you can google “child relaxation scripts” to source some free stories to read. You might even like to write your own! 3 Let worries fly away Teach older children to identify and let go of worrying thoughts with the help of balloons and a Sharpie (permanent marker). Encourage your child to blow up a balloon (you can help of course) and hold the end tight in one hand. Use a black or dark coloured Sharpie to write or draw the worry on the balloon. It could be a word or a sentence or a picture of whatever is on their mind. If your child has difficulty putting their worry into words you can help model what a worry might sound like in your head by writing your own worry. Using the phrase “what if…” can often help get your child started. Once your child has written or drawn the worry, tell your child to let it go and watch it fly around the room. When you retrieve the balloon your child will find that their written worry has shrunk and the writing is very tiny on the balloon – almost as if the worry is not so big anymore. 4 Change a scary image into a funny or silly one Help your child take control of a scary image in their head by teaching them to change what they see. Some children find that bedtime prompts them to think about the scary stories they have seen on TV, read in books or heard from other kids. Children might close their eyes and see an image in their head that is hard to shake (e.g., monster, ghost, zombie etc,). Encourage your child to draw what they see on a piece of paper. Children often find this hard to do as it asks them to face their fear directly. Once the image is drawn tell your child to change the image so they find it funny or silly. For example, one child kept picturing a zombie in her head when she closed her eyes at bedtime. Using the drawing technique she was able to turn the image into a zombie dancing gangnam style and she no longer found it so scary. With repetition, every time the zombie entered her head she thought about him doing gangnam style and it stopped keeping her awake. Read more on supporting your child through nighttime fears 5. Schedule worry time Help older children manage their worries at bedtime by encouraging them to schedule “worry time” into their day. Just like many adults, bedtime can be a time when the mind gets busy. Encourage your child to engage in a scheduled “worry time” earlier in the evening (instead of just before sleep). Your child can write down or say their worries at a scheduled time (e.g., just before dinner, after school or before the bedtime routine starts). Technology can be helpful here – your child can use a tablet or phone to record themselves (e.g., on apps like voice notes) saying their worries. Your child can then listen back to their spoken worries and then switch them off. Switching off a device is much easier than switching off a busy mind! Worries at bedtime are common for children. Teaching your child different ways of managing their worries can help them to relax as they go to sleep and teach important skills for self-regulation. If you are concerned about your child’s worries please seek professional advice. At Hopscotch and Harmony we have child psychologists who can help children and parents learn to manage worry. To book an appointment at our Werribee practice please contact us on 9741 5222. About the author:

Written by Jessica Cleary, Psychologist How did your kids go at the beginning of the new school year? If you do kinder or school drop-off you will have noticed some kids take the new challenge in their stride, whereas others have a much harder time with the transition and separation from their mums and dads.

Maybe you found yourself with a little one who was crying and clinging and begging you not to leave. I feel for you if this was the case – it’s so hard! Or maybe your child complained of tummy-aches or headaches before leaving home. This is a common symptom of anxiety. It’s fairly common for some kids to have troubles adjusting to school. Although there is no magic solution when supporting your child through separation anxiety, here are some ideas for you: Find a friend It helps immensely when kids have a friend at school. Ask the teacher who your child seems to play with the most and introduce yourself to the parent at either drop off or pick up. Arrange a play date over at your house or a park to help nurture that relationship. Talk about it ahead of time If you know that tomorrow is likely to be another morning of tears and clingy behaviour then talk about it today when you are both feeling calm and relaxed. When children fear something they need the opportunity to express their feelings. Some of his worries or concerns may seem small or insignificant to us, but for him they are very real and should be respected. It is important to acknowledge that the feeling of worry is very real for your child. Then focus on solutions to the problem. Highlight the fun parts of the day like playing with a friend or lunchtime. Remind him that after a little bit of upset he was able to enjoy the school day and he got to do new and exciting things. Let him know that you will ALWAYS come back. Team up with the teacher Work in partnership with the teacher. Experienced teachers have been through this before so are likely to have a few good ideas. If the separation anxiety doesn’t ease after a few days the teacher may be able to give your child a special job to do immediately upon getting to school. This will serve as a transition activity and is something for him to look forward to. Get to school early so the teacher can personally greet your child and take him to the activity. Don’t focus on the separation On the way to school talk about the first thing your child will do once he gets in the classroom. It shifts the focus from the separation to the enjoyable activity. This helps him mentally prepare before he is physically at school. He starts to visualise the inside of the classroom and can start to get used to the idea of being there. Something like this: “When you go to the reading corner, what book are you going to read first?” or “Which colouring in page will you choose when you get there – the train or the castle?”. Or if you have an arrangement with the teacher (see previous tip) you can talk about this with enthusiasm. Don’t talk about ‘school’ At home in the morning, don’t talk about ‘school’ too much. Talk about ‘reading time’ and ‘drawing’ and 'play time’. Talk about that first activity that he will be doing with the teacher (if you have one planned). The word ‘school’ may currently have a negative, anxiety provoking association for your child so avoid it if possible. Instead talk about the activities he will be doing at school that you know he enjoys. This makes the idea of school more concrete and less abstract. Transitional objects A special note from you kept in his pocket, or matching love hearts drawn on his and your hand can help your child feel connected to you during time apart. Other issues Sometimes separation anxiety occurs in the context of more generalised anxiety or trauma. Maybe there is a real problem at school that is causing distress. Listen carefully to your child and do a little detective work if you sense there is more to the story. Could it be that he doesn’t know how to ask to go to the toilet? Or is he being bullied? Does he find it hard navigating the school grounds at recess? Listen carefully and get more information from the teacher to help you work out what the underlying problem may be. When to seek professional support Often patience and using the above tips can ease separation anxiety. However, there are times when it is necessary to reach out for additional support. You may need further help if:

Finally Remember, your child isn’t trying to manipulate you. The feelings are real for your child and quite distressing. Although you may not always be able to prevent the separation anxiety, you can always empathise with your child and connect with him with cuddles and snuggles at the end of the day. You wouldn’t be the first parent to cry on your way to work after holding it together at school drop-off. This experience is so very stressful for parents. Look after yourself to help manage your own stress. Sleep and eat well and talk to a trusted friend who will listen and support you. Taking care of yourself and allowing yourself your own emotional release will help keep you centred and more emotionally available for your child. It’s common for parents to feel concerned when their child is worrying too much. You may wonder whether it’s just a phase or whether things are going to get worse. You may feel powerless to help your child feel better. We all know what it’s like to feel anxious and stressed and, if you are like most parents, you desperately want to relieve your child from this discomfort. Here are some ways in which you can help:

|

Categories

All

|

Hopscotch & HarmonyAt Hopscotch & Harmony Psychology, you can expect compassionate care and evidence-based guidance on your journey to wellness.

With clinics in Werribee and Belmont, as well as providing online counselling to clients who live throughout Australia, our dedicated team of psychologists and dietitians are committed to providing support to children, teenagers and adults. With a focus on understanding your unique needs, we offer tailored solutions to foster growth and resilience. Trust in our experience and dedication as we work together towards your well-being. Welcome to a place where healing begins and possibilities abound. |

Our services |

Contact usHopscotch & Harmony

Child, Teen and Adult Psychology Our Locations:

WERRIBEE: 1/167-179 Shaws Rd

BELMONT: 92 Roslyn Rd AUSTRALIA-WIDE: Online counselling |

Hopscotch and Harmony respectfully recognise the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people as the first Peoples of the continent now called Australia.

We acknowledge the Bunurong and Wadawurrung people of the Kulin Nation, the traditional owners of the land on which we work, and pay our respects to their Elders, past, present and emerging.

© 2024 Hopscotch and Harmony Pty Ltd

RSS Feed

RSS Feed