|

A cognitive assessment is a type of evaluation that measures a person's thinking abilities and intellectual potential. It typically includes a battery of tests that assess different areas of cognitive functioning, such as attention, working memory, processing speed, language, and problem-solving. As part of the assessment your clinician will undertake a parent interview to gather information about the child’s developmental trajectory and identify any factors that may have influenced their development. Cognitive assessments can be useful for identifying a child's strengths and weaknesses, as well as for identifying any learning difficulties or intellectual developmental delays. This information can help educators and parents better understand the child's learning style and needs, and can guide the development of individualised educational plans. Cognitive assessments can also help identify giftedness or advanced abilities in specific areas, which can guide the development of advanced or accelerated educational opportunities for the child. In addition, cognitive assessments can be used to monitor a child's progress over time, and can provide insight into the effectiveness of interventions or accommodations that are put in place to support the child's learning. Overall, a cognitive assessment can provide valuable information that can help parents and educators better understand a child's learning profile and tailor educational strategies to best meet their needs. Areas of cognitive functioning: Verbal Comprehension: Measures the ability to understand and use language, including vocabulary, grammar, and comprehension. Perceptual Reasoning: Measures the ability to solve visual problems and spatial reasoning, including the ability to recognise patterns and solve visual puzzles. Working Memory: Measures the ability to hold and manipulate information in the mind, such as remembering a series of numbers or letters. Processing Speed: Measures how quickly a person can process information and respond to it. Fluid Reasoning: Measures the ability to reason and solve problems using abstract concepts and logic. The importance of noticing the ‘grey area’ children in a black and white education system.29/1/2019

In a funding based educational system, it can be challenging for teachers to adequately support students who they have identified as having significant educational needs, however were not eligible for funding under their education system. Without dedicated funding and limited resources to support the particular student, teachers often report feeling somewhat helpless. In these cases, teachers tend to feel that the demands of the curriculum are forever exceeding the level of the student’s abilities and that the child is not receiving a satisfactory amount of support in accordance with their educational needs. In addition, the students themselves begin to feel discouraged at school, as their academic successes are inconsistent and subpar compared to their peers. This can lead to feelings of stress, poor self-efficacy and poor self-esteem. While acknowledging that each student and their circumstances are unique, there are some simple steps that school staff alongside parents can take to facilitate discussion about the student’s needs and begin planning for appropriate interventions within the resources available. 1: Be self-forgiving. In most cases, it is a reality that the level of adjustments required to extensively support this child may be beyond what you as one person (with 20+ students to simultaneously support) can achieve in a classroom setting. Be prepared to accept that your absolute best efforts as a teacher may only account for a portion of the adjustments that the child requires. 2: Assessment. The first step to providing individualised support to a student with educational needs is to understand what their unique learning needs are. The type of assessments that will be completed/sought will depend on the presenting concerns (medical, language, cognitive, sensory etc.). For example, children who experience difficulties with comprehension/with their expressive vocabulary may benefit from a language assessment. It is more than likely that if a child has been identified as having significant educational needs that standardised assessment would have already been completed to identify the specific strengths and targets for intervention of the child. Usually children with identified difficulties in school systems are referred for a cognitive (or psychoeducational)/language assessment (depending on the presenting concerns) which is usually completed by the Psychologists/Speech Pathologists in the Student Support Services team. This service is of no cost to the family/school, however waiting periods may vary. Once school staff and parents are aware of the child’s level of functioning in the relevant areas, individualised support planning can commence. 3: Plan. A collaborative support system (containing teachers, parents and external service providers if any) for these children is essential in supporting the student’s unique needs. It is important that this support system discuss each area of development and who/what will be responsible for this aspect of intervention. For example, if it was identified that the child has complex sensory needs, then a classroom sensory diet can be developed in conjunction with an external Occupational Therapist and implemented by the classroom teacher daily. In addition, a Psychologist may suggest appropriate social-emotional strategies that can be implemented in a classroom setting. To facilitate discussion about the unique needs of your student, I have summarised just a couple of general examples of recommendations that may be suggested in a planning meeting. However, it is important that the support team maintain their unique goals to one or two important objectives at a time and do not overwhelm the student with too many interventions at any one time. Communication

Sensory

Social-Emotional / Behavioural

Educational

4: Review and Revise Pay attention to how the student is responding to the planned interventions and seek to implement these consistently for a minimum of four weeks. Review the student’s progress with the support team and make revisions to the approach/interventions as required. It is also important that progress is reflected on and the interventions evaluated by the child themselves. Overall, it is vital that the support team work hard to ensure that the student feels supported and successful in order for them to thrive from appropriate intervention. We can all agree that the ‘school world’ children live in today is completely different to ours ‘back in the day’. There are notable differences in the subjects studied, classroom layout (assigned desks vs flexible learning spaces), interests (outdoor cricket vs Minecraft), jargon used (“the bomb” vs “lit”), technology available and teaching methods provided to students (blackboards and paper vs interactive whiteboards and iPads). Consistent with these changes, there has been a shift in the way we think about and assess children’s progress, thinking and learning in school settings. Imagine that you have a son named ‘Johnny’ in Grade One. He is a vivacious and affectionate boy who loves sports and enjoys going to school. His teacher has completed her usual assessments to determine Johnny’s progress in fundamental subjects (reading, writing and maths). From Johnny’s previous school reports, you’re concerned that he’s performing below standard and don’t want him to fall behind further. One day, Johnny’s teacher and Assistant Principal sit you down and ask you to sign a consent form as they believe that given Johnny’s difficulties he may benefit from a Cognitive assessment and/or Oral Language assessment. At this point you’re thinking, my son would benefit from what? Why? How is this going to help him? The ‘What’. What are they talking about? First off, let’s define cognition. Cognition is our mental process of not only acquiring information, but making sense of it. Do these assessments have a name or is it just ‘cognitive assessment’? The most commonly used cognitive assessments in Victorian schools are:

For children in Years 11 and 12 there is the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS-IV) for individuals aged 16.0 to 90 years 11 months. However, it is rare that cognitive assessments at this age are administered for educational purposes. Cognitive assessments (or intelligence tests/IQ tests) are used in school settings to assess a child’s level of overall cognitive (aka mental) ability, learning capacity and identify their cognitive strengths and weaknesses (for example, does your child thrive with visual information? Are they good at problem solving? Do they better deal with verbal information?). What do these assessments measure?These assessments measure cognitive abilities within 5 primary indexes, or ‘areas’ of intelligence:

There are many other ‘ancillary’ or ‘other’ indexes that can also be calculated, however it’s not a ‘need to know’ for now. If relevant to your child’s case the Psychologist can explain it to you. The assessment within a whole processThe cognitive assessment itself is actually NOT the only thing Psychologists do when they conduct a cognitive assessment. Here is a brief dot point summary of the process:

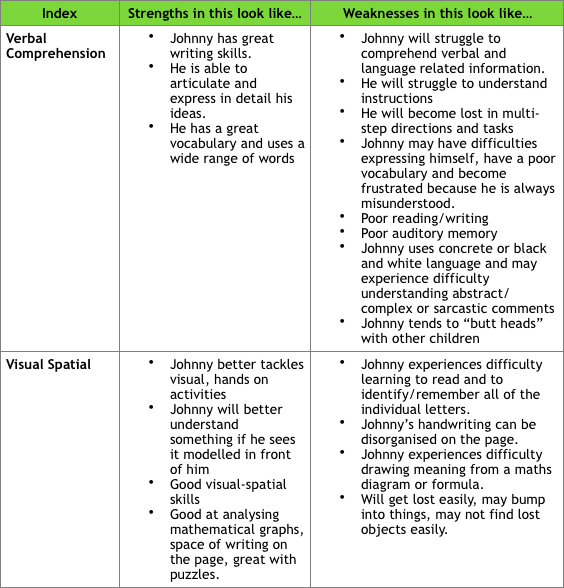

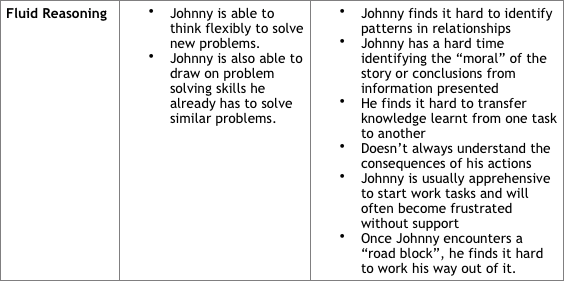

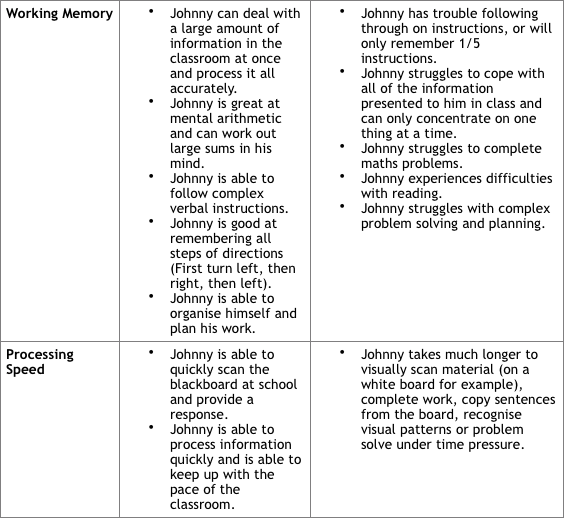

Now, depending on the unique situation of your child, there may be other things that occur alongside this ‘standard process’. For example, if you’re looking to obtain funding through the school system for Intellectual Disability, a Psychologist would have to complete other assessments AS WELL as this and write a separate funding report. Cognitive assessment, part of a formulaIt is quite often that the entire cognitive assessment process (from parent consult onwards) is paired with other standardised assessment for different referral questions. Here is a brief snapshot. Intellectual Disability: Cognitive Assessment + Adaptive Functioning Assessment Language Disorder: Cognitive Assessment + Language Assessment Specific Learning Disorder: Cognitive Assessment + Achievement Assessment (sometimes memory assessment and phonological awareness testing is also included) Giftedness: Cognitive Assessment + Gifted Rating Scales or other information gathering The ‘does this ring a bell?’ gameA good way to understand the abilities that cognitive assessments measure is to know what the “strengths and weaknesses” in these skills actually look like in school aged children. Have a look at this table and see if any of these ‘ring a bell’ or ‘ring true’ to your child. Now that we understand what it measures, how do I make sense of these results?A lot of scores come out of cognitive assessments, however I feel that parents should be knowledgeable of two things: Percentile Ranks Percentile ranks reflects how a child performed compared to children the same age. Let’s say we lined up 100 boys the same age as Johnny in order of ‘ability. The little boy sitting at position 1 would be the worst performing and 100 the best. If I told you that Johnny was sitting at the 50th percentile, it means that he is RIGHT in the middle and performing as he should be for his age OR that he is performing better than 50% of children his age. With cognitive assessments, the Average Range falls within the 25th to the 75th percentile. Standard Scores Put simply, standard scores are these converted scores that Psychologists use to determine where Johnny’s cognitive abilities lie in comparison to other children his age and what range of ability he falls under. You’ll see ranges associated with standard scores for the indexes and Full-Scale IQ. As an example, any standard score between 90 and 109 falls within the Average Range. Here is a general scoring guideline table for quick reference: What do schools do with cognitive assessment results?Psychologists make recommendations that teachers can use to develop a personalised learning plan for the child. These recommendations are made based on your child’s strengths and weaknesses. As a very simple example, Johnny might have a personal strength with visual-spatial skills but weaknesses in working memory. The psychologist might then recommend that all instructions provided to Johnny in the classroom be concise, clear and provided to him one at a time. The psychologist might also recommend that instructions or demonstrations in the classroom be highly visual in nature when being delivered to him or that verbal instructions are paired with visual stimuli. Depending on the reason for the referral, these results and the report might be passed onto a paediatrician or submitted as evidence for a funding application within the Victorian school system. The cognitive assessment process is a highly rewarding one. It provides educators and parents with the opportunity to better understand the learning needs of the child involved, and also to address your concerns as parents about why they are falling behind academically. At Hopscotch and Harmony, we have a team of Psychologists including myself who are highly experienced in conducting cognitive assessments and thoroughly enjoy collaborating with parents and educators to achieve the best outcomes for children. To make an appointment, please don’t hesitate to ring us on (03) 9741 5222. I have developed a “Guide to cognitive assessment: A cheat sheet” as a resource for schools and parents. This provides a brief snapshot of the content in this blog post. I hope you find it useful! |

Categories

All

|

Hopscotch & HarmonyAt Hopscotch & Harmony Psychology, you can expect compassionate care and evidence-based guidance on your journey to wellness.

With clinics in Werribee and Belmont, as well as providing online counselling to clients who live throughout Australia, our dedicated team of psychologists and dietitians are committed to providing support to children, teenagers and adults. With a focus on understanding your unique needs, we offer tailored solutions to foster growth and resilience. Trust in our experience and dedication as we work together towards your well-being. Welcome to a place where healing begins and possibilities abound. |

Our services |

Contact usHopscotch & Harmony

Child, Teen and Adult Psychology Our Locations:

WERRIBEE: 1/167-179 Shaws Rd

BELMONT: 92 Roslyn Rd AUSTRALIA-WIDE: Online counselling |

Hopscotch and Harmony respectfully recognise the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people as the first Peoples of the continent now called Australia.

We acknowledge the Bunurong and Wadawurrung people of the Kulin Nation, the traditional owners of the land on which we work, and pay our respects to their Elders, past, present and emerging.

© 2024 Hopscotch and Harmony Pty Ltd

RSS Feed

RSS Feed