|

Parenting in the age of social media presents its own unique challenges. It's essential to recognise that as parents, you're navigating uncharted waters alongside your teens. Here are some compassionate and validating tips on how to support your teen in this digital age:

Model Healthy Habits: We often underestimate the impact of our own actions. Your teen looks up to you, so start by acknowledging that it's not easy for anyone to resist the lure of social media. Share your own struggles and triumphs in managing screen time. By modeling healthy social media habits, you're showing your teen that it's perfectly normal to have boundaries and take breaks. Understanding the Highlight Reel: Social media can be a breeding ground for comparison and self-doubt. It's crucial to discuss with your teen that what they see online is often a carefully curated version of reality. People tend to share their best moments, not their everyday challenges. Encourage your teen to see beyond the filters and highlight reels. Validation of Feelings: Your teen's emotions around social media are valid. It's okay for them to feel overwhelmed or anxious about it. Let them know that their feelings are understood and respected. This open dialogue can foster trust and make them more comfortable discussing their online experiences with you. Authenticity Matters: Emphasise to your teen that authenticity trumps perfection. They don't need to conform to unrealistic standards. Encourage them to be true to themselves and remind them that it's their unique qualities that make them special. Being authentic is far more valuable than striving for a "picture-perfect" image. "Disconnect to Connect" Time: To strengthen family bonds, consider setting aside dedicated times when everyone disconnects from devices and focuses on connecting with each other. Dinner time is an excellent opportunity for meaningful conversations. Encourage your teen to share their achievements, no matter how small, and celebrate their strengths. Active Listening: When your teen shares their wins or concerns, be an active and empathetic listener. Show genuine interest in their hobbies, interests, and aspirations. Ask open-ended questions and provide a safe space for them to express themselves. Addressing Challenges: Life isn't all about victories; it's also about overcoming challenges. Encourage your teen to open up about their struggles, assuring them that it's okay to seek help when needed. Your unwavering support will help them navigate life's hurdles with confidence. Consistency is Key: Make "disconnect to connect" time a regular part of your family routine. Consistency reinforces the importance of face-to-face interactions and sends a powerful message that your teen's well-being and experiences matter. Talking about Fabrication: Engage your teen in critical thinking about what they see on social media. Encourage them to question whether posts truly represent someone's life. Share your own experiences where social media didn't reflect reality, demonstrating that even adults are not immune to these illusions. Embrace Individuality: Finally, empower your teen to focus on their own values and interests rather than comparing themselves to others online. By helping them understand the constructed nature of social media, you're guiding them towards a stronger sense of self and confidence in their choices. Discovering your adolescent is self-harming can be very confronting. It can bring up feelings of powerlessness, but there are things you can do to support your adolescent.

1. Listen without judgement Adolescents who self-harm may feel ashamed, embarrassed, or frightened to talk about it. Therefore, it is essential to create a safe and non-judgmental environment that promotes open communication. 2. Help them identify triggers Encourage your adolescent to identify what triggers their self-harming behaviour. These might be topics, situations or feelings. Support them in finding healthy coping mechanisms to deal with these triggers to replace the self-harming behaviour. 3. Encourage them to seek professional help Self-harm can be a sign of underlying mental health issues such as anxiety, depression, or trauma. Encourage the adolescent to seek professional help from a therapist, counsellor, or psychiatrist. 4. Teach relaxation techniques Support your adolescent to learn relaxation techniques such as deep breathing, meditation, and progressive muscle relaxation to help them manage their emotions and reduce anxiety. 5. Encourage positive self-talk Encourage your adolescent to replace negative self-talk with positive affirmations. This can help boost their self-esteem and reduce the urge to self-harm. 6. Provide a distraction When the adolescent feels the urge to self-harm, provide them with a distraction such as going for a walk or doing a fun activity to take their mind off the urge. 7. Offer unconditional love and support Finally, offer your adolescent unconditional love and support. Let them know that you are there to help them through this difficult time and that they are not alone. The experience of losing a loved one to death, the many months and years that pass, are clearly profound, and often difficult times for families, including children. Talking to children about death is a difficult and sensitive topic for many parents. It can also build connection, trust and support within families. By having an open and honest conversation with your children, you can help them understand and process the loss of a loved one. In this blog post we will explore some tips for talking to children about death. Trust your own culture and family traditions, instincts, beliefs and spirituality. It can sometimes feel like we need a ‘best’ or a ‘normal’ way to approach the topic of death, but the truth is we are all learning to do this together. If you are unsure about how to talk to your own children about death, you may like to reach out for professional advice, but you may equally find the answers inside your family, a close circle of friends or your community. Use clear and age-appropriate language. When talking to children about death, it’s important to use clear language. It’s often best to avoid ambiguous language and euphemisms. Using phrases such as “went away” or “went to sleep” may lead to confusion and difficulty for children, given the overlap of these concepts with other everyday experiences. It is possible that this confusion might lead to more fear and anxiety, rather than understanding. Be honest and open It’s important to be honest and open with children, when talking about death. Children will naturally have questions, if not immediately, then after they have given things some thought. Children are very thoughtful and perceptive, if we are not honest they may sense that something is wrong. It can be best to be open with them, to build trust, encourage a sense of safety, connection and understanding. Validate their emotions. There is no rule book for feeling and navigating the profound experience of loss, and the feelings can change over time. Children may be watching other family members, and wondering if they are reacting ‘properly’. It’s important for children to know that there is no correct way to feel, that things may feel surprisingly easy for a time, or very difficult, on and off, for a while. Notice your own needs. Talking to children about death may be one of the most difficult conversations you ever have. Answering their questions, and validating their emotions, whilst organising and balancing all of the other needs and demands placed in front of you, is likely to have an effect on you at some point. It may be that you do well in the moment, and later realise your own needs, or maybe you need self-care, self-compassion and support right away. Either way, be kind to yourself, and seek what you need, when the time is right for you. Seek professional help if necessary. Experiencing great challenges and changes in these major life moments is normal. Supporting children through these moments is also normal. However, if your child is having a hard time coping, and you feel like you could use some extra support, a psychologist can support parents, help your child process their emotions and develop healthy coping strategies. Tim Walker

Psychologist As a parent, it can be tough to see your child struggling with emotional or social difficulties. You want to help them, but sometimes it's hard to know where to start. That's where psychological therapy can come in. If you're considering bringing your child to their first session at Hopscotch and Harmony, it's natural to wonder what to expect. In this blog post, I'll walk you through what your child's first therapy session might look like. Before the Session Before the session, you'll have some online forms to fill out. This will include things like your child's medical history, any medications they're taking, and details about their presenting challenges. It's important to be as honest and thorough as possible when filling out these forms as the more information your therapist has, the better they'll be able to help your child. The Initial Session The first session is usually a parent/carer only session. This is an opportunity for the psychologist to get to know you and to gather more information about your child’s challenges and strengths. The psychologist may ask you some questions, such as:

The Therapy Session After the initial session, your child will begin their therapy sessions. These sessions may be individual, family-based, or a combination of both. During the first therapy session, your child and the psychologist will likely engage in games and fun activities to begin building rapport and developing a therapeutic alliance. It's important to understand that therapy is a process, and it may take time for your child and you to see progress. The psychologist will work with you and your child to set goals and track progress, so you can see how your child is doing. Taking your child to their first psychological therapy session can feel daunting, but it's an important step towards helping them better understand themselves and improve their well-being. By being open and honest with your psychologist and supporting your child through the process, you can help them build the tools they need to thrive. It might also be helpful to show your child the profile of their clinician on the Hopscotch and Harmony website to help subside any nerves prior to the first session.

One in three women in Australia will experience a loss during pregnancy. Often it can be incredibly personal, and devastating. But everyone’s experience is unique, as are their feelings about the loss and how they chose to grieve. If someone you know has chosen to let you know they have had a recent miscarriage or suffered a loss during their pregnancy, it can be difficult to know what to say. Avoid saying…”At least you know you can get pregnant.” Why not? This may be the woman’s first or fifth pregnancy loss. Being able to ‘get pregnant’ may not be the concern and saying this minimises the loss. Instead try… “I am so sorry for your loss.” Avoid saying… “It just wasn’t meant to be.” Why not? Often the reasons for miscarriage are unknown. Such statements do not make the loss easier, and the woman may not have the same beliefs as yourself. Instead try… “How are you feeling? I am here if you need to talk or I can give you space.” Avoid saying… “It isn’t like you lost a baby, it was just cells at this stage.” Why not? A loss, no matter how small, can still feel monumental and can be grieved. Instead try… “I am here if you need - whatever you need just let me know.” Avoid saying… “Next time you should, “...”, it will help you stay pregnant.” Why not? Chances are the person has already looked into every trick under the sun, medical or alternative, to help their pregnancy progress, and may be placing a lot of blame on themselves already. Instead try… “It wasn’t your fault, you did nothing wrong.” Avoid saying… “I knew someone who had 3 miscarriages and now they have 2 healthy children.” Why not? This is their experience, not yours. Most people do not want to be reminded of the ‘successful; pregnancies as they are going through a loss. Instead try… “My heart hurts for you right now. I love you and you are are allowed to be sad.” Avoid saying… “Lots of women have miscarriages. You just have to pick yourself up and keep going like everyone else does.” Why not? Everyone experiences grief differently. While normalisation can be a comfort, feelings should not be minimised. Instead try… “Grief can be really hard. Take the time you need.”

Are you concerned about your child or teenager and aren’t sure if a psychologist is right for them?

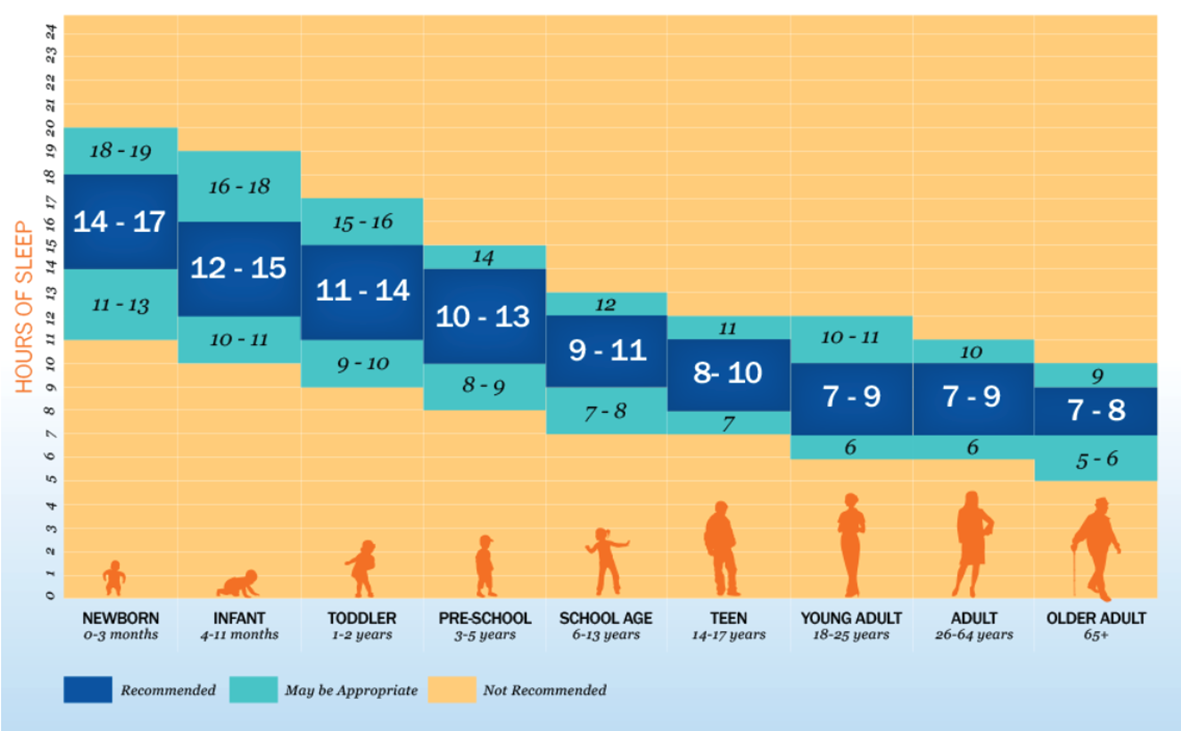

Psychologists can help people in many different ways and support looks different for each individual. A psychologist can provide a range of support and guidance for young people who are experiencing emotional, behavioural, or mental health issues. When you take your child to see a psychologist, they will work with you to create specific treatment goals tailored to your child’s individual needs and challenges. Here are some ways that a psychologist can help your child: Assessing and diagnosing mental health conditions: A psychologist can conduct assessments to diagnose mental health conditions, such as anxiety, depression, ADHD, or eating disorders, which can help guide treatment and support for your child. Developing coping skills: A psychologist can work with your child to develop healthy coping skills for managing difficult emotions, such as anxiety or anger, which can help them feel more confident and resilient in the face of challenges. Providing therapy: A psychologist can provide therapy for your child to help them work through specific issues or challenges, such as difficulty with social relationships or school-related stress. Teaching problem-solving and decision-making skills: A psychologist can teach your child effective problem-solving and decision-making skills, which can help them navigate difficult situations and make healthy choices. Providing parenting support and guidance: A psychologist can work with you as a parent to provide support and guidance for helping your child develop healthy habits and coping strategies. Remember, it's important to approach the topic of seeking help with warmth, empathy, and understanding. By doing so, you can help your child feel more comfortable and supported as they navigate their emotional well-being. Overall, a psychologist can provide unique support and guidance for your child based on their individual needs, and can work collaboratively with you and your child to help them develop the skills and resources they need to thrive. A tantrum is an outburst of intense, emotion-driven behaviour that can be exhibited by young children. They typically start between the ages of 1 and 4, and can last well into later childhood years. A meltdown is ALSO an intense and overwhelming emotional response that can be exhibited by individuals, but they can occur at any age, and are more commonly associated with neurodevelopmental conditions such as autism, sensory processing disorder, ADHD, anxiety, as well as some mental health difficulties, such as PTSD. During both tantrums, and meltdowns, an individual may scream, cry, kick, throw objects, hurt themselves accidentally or on purpose, or withdraw and seem to shut down. Tantrums can occur in response to frustration, anger, or other strong emotions, and can be triggered by a variety of factors, such as hunger, fatigue, overstimulation, or a desire for attention or control. Tantrums are a normal part of child development and can be a way for children to express their emotions when they do not yet have the language skills to do so effectively. Meltdowns can also be triggered by a variety of factors, such as sensory overload, emotional stress, changes in routine, or difficulty with communication or social interaction. In both tantrums and meltdowns, the behaviours can be distressing for both the individual experiencing the difficult emotions, and for those around them. And it’s important to note that something might start as a tantrum, but as the individual becomes increasingly overwhelmed by their emotions and the bodily sensations and stress these bring about, they might move into meltdown. In either instance, we need to understand that the child or individual isn’t behaving this way on purpose and that they feel awful. Nobody likes having these strong and overwhelming emotions, and most of us want to feel calm and happy rather than angry and upset. A calm, compassionate, and curious approach to individuals who are experiencing strong emotions is often the fastest way to both help them back to calm, and understand what happened to them. If you or your child are struggling with tantrums or meltdowns, you might like to have a look at our Director, Jessica Cleary’s evidence-based Calm and Connected Parenting Program to help you understand what’s going on, and to calm the chaos. You can find a link HERE. Sleep is very important. Studies have consistently shown that sleeping well improves mood, emotion regulation and our cognitive processes such as problem solving and decision making, while poor sleep can have the opposite effect. But how much sleep do we actually need? And, does this amount change across our lifespan? According to the American Academy of Sleep Medicine Guidelines, the amount of sleep we need does in fact change over time. During the first years of life, infants and toddlers are recommended to sleep between 11-17 hours over a 24 hour period, with the total amount of recommended sleep steadily declining over time. Primary school aged children should sleep between 9 and 11 hours a night (at which time daytime naps generally no longer occur), while adolescents should sleep between 8 and 10 hours a night. It isn’t until we reach the age of 18 that sleep recommendations become more consistent until the age of 65 (7 to 9 hours a night), when there is another decline in the number of recommended hours of sleep (7 to 8 hours). Natural changes in sleep also occur with age. For example, during adolescence, melatonin production (the hormone your body produces to make you feel tired), occurs later, making it difficult for teeangers to go to sleep earlier at night and difficulty waking up early. Another example is when we enter older adulthood (65+ years), it is normal to have a tendency to engage in lighter sleep with more awakenings. However, worrying about these changes when they occur can lead to the development of conditions like insomnia as older adults feel concerned that they aren’t getting enough ‘good, normal’ sleep. There can also be many reasons why we may not be getting enough sleep. These reasons can be biological (genetics, due to medication, hyperarousal), psychological (worry, stress) or social (shift work, commitments, technology use, poor sleep habits). It is also important to note that just as sleeping too little increases the risk of physical and mental health problems, sleeping too much may be a sign of other ongoing health concerns, resulting in increased levels of fatigue. If you consistently feel tired or unrested after sleep, speak to your doctor about possible causes.

Bullying is a serious issue that can have a lasting impact on mental health and wellbeing. As a parent it can be heart-breaking to learn that your child is being bullied. We all want the best for our children. We often wonder how they are going at school, hoping for them, and wishing for them a rewarding and safe experience. If you have learned that your child is being bullied at school, there are steps you can take to support your child and address the situation. In this blog post, we’ll explore some tips for what to do if your child is getting bullied. 1. Listen to your child The first step is to listen. Your child may feel confused, scared or even ashamed. If they are telling you they are being bullied then they are demonstrating bravery and self-protection. It is important to acknowledge and reward your child for this healthy, brave behaviour. Encourage them to share their experience without judgment. Validate their emotions and let them know what is happening to them is not ok. Let them know you and the school are going to help make a change. 2. Contact the school and advocate for change Schools have an enormous responsibility. Document the bullying. Contact the school. Speak to educators and administrators that are directly responsible for safety. Talk with educators that know and care about your child. Arrange for a meeting with the teacher, principal, school counsellor, and/ or wellbeing coordinator. Share your concerns and provide any documentation you have. Ask the school directly, what is their bullying and safety policy? Ask what steps the school will take to address the bullying and how they will support your child. 3. Assess the level of risk If it is not safe for your child to attend the school, the school needs to be aware of your concern. If you are confident the school is taking steps to protect and support your child, you may like to follow up, check to see what steps have been taken, and continue advocating for change. 4. Teach your child coping skills Bullying can have a significant impact on self-esteem and confidence. You may have your own coping skills to share, perhaps your child already has a set of excellent skills for resilience and managing adversity. You might like to find and explore resources together online, in books, podcasts, or elsewhere. Encourage them to engage in activities they enjoy, celebrate who they are, spend time with supportive family and friends, or express themselves through art, sport, writing or music. 5. Seek professional help if necessary If your child is struggling to cope with the bullying experience, this is normal. You may need extra time, resources or support. If your child is experiencing significant mental health effects, a psychologist can provide support by teaching your child additional coping strategies, and offering a safe place for them to process the experience and supporting parents. The Victorian Government provides a number of practical steps and advice for parents, schools and teachers to support children who have experienced bullying. You may like to explore the website here https://www.vic.gov.au/bully-stoppers written by Tim Walker

Provisional Psychologist Parent engagement is an important part of therapy with children, and can help ensure the best possible outcomes for the child and family. By working together with your psychologist/clinician, parents can play an active role in supporting their child's mental health and well-being. Parents provide valuable information: Parents know their children better than anyone else and are a key source of information about their child's behaviour, emotions, and experiences. By sharing your observations and concerns you help your clinician gain a better understanding of your child's needs and goals, and develop an effective, accurate treatment plan. Enhances treatment outcomes: Research has shown that parent involvement in their child's therapy can lead to better treatment outcomes. When parents are actively involved in the therapy process, they can reinforce the skills and strategies learned in therapy at home, which can help their child and the family make progress more quickly. Increases motivation and engagement: Children are more likely to be motivated and engaged in therapy when their parents are involved. When parents participate in therapy sessions, it can help the child feel supported and comfortable, and encourage them to participate more fully in the process. Supports ongoing progress: When parents are involved in their child's therapy, they can better monitor their child's progress and identify any areas that may need additional attention. This can help the clinician adjust the treatment plan as needed and support ongoing progress that meets your family’s needs. Having your child come out to you as transgender can bring up complex and challenging emotions. 1. Listen to them. Let your adolescent know that you are there to listen and support them, and make sure they feel heard and validated. Approach them with curiosity rather than criticism, even if you do not agree with them. It’s likely they have thought long and hard before coming to you, and it’s not an easy conversation for them to start. Remember they are not coming to your to ask for your permission or approval, they are telling you who they are. 2. Respect their identity. Respect your adolescent's gender identity, even if it's different from what you expected or are comfortable with. Practise using the pronouns and name that they ask you to use, and correct yourself when you slip up. 3. Provide a safe and supportive environment. Create a safe and supportive environment for your adolescent, both at home and in public settings. Discuss with your adolescent how you can best support them by speaking to their school, workplace, friends and family members. 4. Educate yourself about transgender issues. Educate yourself about the challenges and experiences of transgender people so you can better understand what your adolescent is going through. 5. Seek professional support for your child. If your adolescent is struggling with their gender identity, seek professional help from a therapist or other qualified mental health professional. 6. Seek professional support for yourself. It is ok to find yourself struggling with your child’s identity. It can be scary and confronting. You might fear for your child’s safety, mourn the child you thought you had, or worry that they will face discrimination throughout their life. Seek support for yourself from a therapist to work through your feelings and concerns around your child’s identity. 7. Don’t assume medical intervention is required. Talk to your adolescent about what they want and educate yourself on what options are available. Your adolescent may not want any medical intervention, or may be wanting to explore options. Medical consultations can be had without any commitment to treatments. 8. Advocate for their rights. Advocate for your adolescent's rights and make sure they have access to appropriate healthcare, education, and other resources. There is a lot of stigma around being transgender and your adolescent may experience rejection, bullying, discrimination or even abuse. They need you in their corner. 8. Connect with other transgender youth and families. Connect with other families with transgender youth or seek out support groups and communities where your adolescent can connect with other trans youth. Sibling rivalry is a common issue in families with multiple children, and can be challenging for parents to manage. Here at H&H we often hear the distress of parents at their wits end and get asked the question “how can I help my children to stop arguing?” Whilst we appreciate that every family situation is unique, here are some tips to get you started in supporting your children in moments of conflict:

So you did it! You’ve been studying for 5 years to become a provisionally registered psychologist and you’re finally ready to apply for jobs. Congratulations! But where-to from here?

As a provisional psychologist in Australia, there are lots of different settings in which you can work to gain the necessary experience and supervision required to become a fully registered psychologist. Some of those setting might include:

Whilst there are many different types of ways that you can work toward your general registration, we like to think that we offer something special at Hopscotch and Harmony. One of the biggest things that we hear from psychologists - provisionally, generally, or endorsed registration - is that they think, or have experienced, private practice as really isolating work, where they’re like ships in the night with their colleagues. They may come into the office, see their clients, do their clinical admin, and head home without ever seeing one of their colleagues during their working day or week. We do things differently at H&H. For a start, we will work with you carefully to ensure that your caseload is made up child and adolescent clients who light you up - rather than groaning as the alarm rings in the morning, you’ll be ready to jump out of bed and start your work day seeing the kinds of clients you love to work with. Secondly, your wellbeing is our priority. We cap the number of clients you see a day at a maximum of 4 early in the internship and 5 later in the internship, so you have plenty of time to work on researching your clients’ presentations, undertaking your clinical admin, and ensuring that you know how to work with each and every one of your clients. We also offer a maximum of 4 client days per week in our internship program, so you can dedicate one day a week to finalising your university studies - because that’s how we need to think of your internship year, the finalisation of all the hard yards you’ve put in at university to date. Third, we make sure that we hire the right kind of people to work at H&H. The kind of people we hire want to work with a team. We offer lots of ways to make sure you have plenty of time to connect with your colleagues. We know that a sense of belonging at work is vital to your wellbeing, and it’s one of our primary priorities. Finally, we pair you with one of our talented, experienced Board-Approved supervisors to ensure that you get your learning and development needs met, and that you’re on track to get through your internship year as close to that 12 month mark as is feasible. If you’ve recently finished your Masters of Professional Psychology and have experience in providing therapy to children and adolescents, and are interested in speaking to us about what we can offer then please get in touch. Our aim is to provide you with the working environment that will help you become a confident, competent, and supported psychologist working in Private Practice, If you have secured an internship elsewhere and are seeking Primary or Secondary supervision in the child and adolescent space then we can help you there too. As children grow up, participating in sports can be an excellent way to develop physical and social skills. However, for some children, the idea of participating in sports can bring about feelings of anxiety and nervousness. It can be challenging for parents to know how to support their child when they are experiencing anxiety in these situations. In this blog post, we'll explore the different ways that children may experience anxiety when playing sport and how Hopscotch and Harmony Psychology can help. Causes of Anxiety in Sport There are many reasons why children might experience anxiety when playing sport. Some common causes include:

Symptoms of Anxiety in Sport It's essential to recognise the symptoms of anxiety in children when playing sport so that you can support them. Some of the signs of anxiety include:

Ways to Help Children with Anxiety in Sport There are several ways that parents and coaches can help children experiencing anxiety when playing sport.

Conclusion Anxiety is a common experience for children when playing sport. It's important to keep an eye out for symptoms and understand the causes so that you can support your child. By creating a safe and positive environment, encouraging your child, teaching relaxation techniques, and seeking professional help when needed, you can help your child manage their anxiety and enjoy participating in sports.

A child’s relationship with food can have a significant impact on their physical health and emotional wellbeing. A child's eating habits are important as unhealthy habits can lead to severe eating disorders in early teen years and adolescence. If you have noticed a change in your child’s eating habits, it is possible that there is an emotional explanation for their behaviour. Here are some factors that could be contributing to distress around food for your child:

Encourage your child to talk about their emotions, and provide support and guidance as needed. By creating a safe and supportive environment around food, you can help your child develop a healthy relationship with food and their emotions. When to seek help from a professional: It can be difficult to know when to seek professional help for your child's eating emotions, as every child is different and may have different needs. However, here are some signs that may indicate that it's time to seek help from a professional:

If you notice any of these signs in your child, it may be helpful to seek help from a mental health professional. They can help you identify the underlying issues that may be contributing to your child's eating emotions, and provide guidance and support for helping your child develop a healthier relationship with food and their emotions. Starting therapy can be scary, especially if you and your child have never done it before. What is going to happen? What am I going to be doing? What am I going to be talking about? Will I like my therapist? Will my psychologist like me? For children, many new experiences can cause emotional responses due to the fear of the unknown. However, there are some things you can do to help prepare your child for their first therapy session to help reduce their worries. Let your child know they are going to see a therapist: a few days before the appointment, sit down with your child during a calm moment and let them know they (and you!) will be going to see a therapist together. Explain the purpose of therapy using simple language, letting them know that therapy is a way for them to talk about their feelings and problems with someone who can help them. Normalize therapy: Let children know that many people go to therapy, and it is not something to be ashamed of. Be positive, encouraging and reassure your child that they can be honest with their therapist because they want to help them. Preparing for the first session: Let your child know what to expect in their first session. At Hopscotch and Harmony, this will generally involve meeting the therapist in a special, safe room, playing games or doing activities, and the therapist asking questions to get to know more about the child. Involve the child in the process: Involve the child in the therapy process by letting them choose a favourite toy or game to bring to sessions or giving them some control over the therapy goals. This can help them feel more comfortable and invested in the process. You can also look at your therapist’s biography on Hopscotch and Harmony’s website to let you child become familiar with the therapist they will be seeing. And of course, your therapist will do everything they can to make sure your child feels comfortable, and safe when they arrive.

Autism, also known as Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is one of many neurodevelopmental conditions. A neurodevelopmental condition affects the development and functioning of the brain and nervous system. Examples of neurodevelopmental conditions include Autism, ADHD, specific learning disabilities (like dyslexia and dyscalculia) and may also include intellectual disabilities. Autism is typically identified through a combination of behavioural observations and diagnostic assessments, observations of the individual to be able to see how it is that they interact with an assessor, their understanding of emotions, their relationships and their part in them, as well as whether they may be experiencing repetitive or sensory seeking behaviours or feelings. An Autism assessment is usually comprised of a couple of different parts: Developmental Screening: Healthcare providers may conduct developmental screening tests to identify any delays in developmental milestones such as language, social interaction, and motor skills. Diagnostic Assessments: If a child is suspected of being autistic, usually their paediatrician will refer the child to allied health professionals for a diagnostic assessment. This assessments may include standardised tests (like the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule or ADOS, or a cognitive assessment - also known as an IQ test), as well as questionnaires, and observations of the child, usually in a clinic environment. The allied health practitioners will then compare the information they have gathered and observed about the child and compare this information with the diagnostic criteria. In Australia the diagnostic criteria most commonly used is from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders - Fifth Edition - Text Revision (DSM-5-TR). Family History and Medical Evaluation: The paediatrician and/or allied health assessors may also evaluate the child's family history and conduct a medical evaluation to better understand the child. Multi-Disciplinary Evaluation: In some cases, a multidisciplinary evaluation may be necessary, involving a team of specialists from different fields such as speech therapy, occupational therapy, and behaviour analysis. Hopscotch and Harmony undertakes assessments from something called a neurodiversity affirmative perspective. The neurodiversity diversity affirmation perspective views Autism as a natural variation in the human brain, rather than as a disorder or a disease. This perspective celebrates the diversity of human thinking styles and recognises that individuals with autism have unique strengths and abilities that should be valued and supported, rather than viewed as deficits that we should be aiming to cure. Autistic individuals may have different communication styles, sensory sensitivities, and ways of processing information, and providing accommodations and support to help them thrive. If you suspect your child may be Autistic, it’s best to first speak to your GP and then a paediatrician. Once you have a referral for an assessment, please reach out to use to make an inquiry about an assessment so that we can help you and your child better understand one another. Helping Teens Through Disappointment: 5 Compassionate Strategies for Uncontrollable Outcomes30/6/2023

by Jessica Cleary, Psychologist Like many parents in Australia I have a devastated teenager in the house after fruitless efforts trying to get Taylor Swift tickets this week. As parents, we strive to support our teenagers through life's ups and downs, including moments of disappointment that are beyond their control. Whether it's missing out on tickets to Tay Tay or facing other circumstances where they have no influence over the outcome, our role as compassionate and loving parents becomes crucial. By providing the right guidance and support, we can help our teenagers navigate disappointment and emerge stronger and more resilient. Here are five tips to assist you in helping your teenager through situations where they lack control, with love and understanding. 1) Practice active empathy: In moments of disappointment, actively empathise with your teenager's feelings and experiences. Put yourself in their shoes and try to understand the depth of their emotions. Let them know that you are there to listen and support them wholeheartedly. By showing genuine empathy, you create a strong bond and provide reassurance that they are not alone in their struggles. 2) Avoid comparisons: Avoid comparing your teenager's disappointment to others' experiences or minimising their feelings. Each person's disappointments are valid and unique to them. Remember that everyone has different expectations and sensitivities, and what might seem insignificant to one person can be deeply disappointing for another. By avoiding comparisons, you create an atmosphere of compassion and respect for their individual emotions. Any sentence that starts with "At least..." is one to be avoided. 3) Encourage self-expression: Once the dust settles a little, encourage your teenager to express their disappointment through creative outlets, such as writing, painting, or playing music. These forms of self-expression can provide a cathartic release for their emotions and allow them to process their disappointment in a constructive way. By embracing their creativity, you empower them to channel their feelings into something meaningful and transformative. 4) Be patient and non-judgmental: It's essential to be patient and non-judgmental when supporting your teenager through disappointment. Avoid offering quick solutions or trying to snap them out of it. It's very uncomfortable for us to see our children distressed so often we can try to shift them out of their 'mood' to ease our own distress. That's not what's needed here. Instead, provide them with the space and time they need to process their emotions and navigate their own path to healing. By demonstrating patience and non-judgment, you foster an environment of trust, emotional safety and unconditional love. 5) Nurture self-compassion: In situations where disappointment arises from circumstances beyond their control, it's crucial to nurture self-compassion within your teenager. Encourage them to be kind to themselves and avoid self-blame or negative self-talk. If you notice any of this type of talk, gently remind them that disappointments are not personal failures and that they are not defined by external outcomes. Teach them to practice self-care and self-compassion by engaging in activities that promote their well-being, such as spending time with loved ones, pursuing hobbies, or engaging in mindfulness practices. It’s so hard to bear witness to our children’s experience of disappointment. Remember that your support and understanding are invaluable in helping your teenager face these challenges and emerge stronger. These practices can help your teenager embrace the uncertainties of life, navigate disappointments, and forge a path towards a fulfilling and resilient future with a compassionate heart.

A sinking feeling. Another phone call from your 11 year daughter’s vice principal. Your loving, funny, and creative child has been accused of messaging a friend a heap of unkind names. She has been identified as a bully. Bully is a word heavy with meaning. It will be helpful to approach the situation with a curious mind, focus on what is in your control, and seek support from others. Behaviour as an iceberg Bullying is a description of aggressive behaviour. Like any human behaviour it can be helpful to approach it with curiosity. Some people find it helpful to visualise an iceberg, with the aggressive behaviour being the tip, or what can be experienced, while your daughter’s motivations lie hidden under the surface. To approach with curiosity try:

Circles of control After receiving a phone call about your child’s undesired behaviour, you may have the instinct to activate panic mode. You might ask yourself a hundred unanswerable questions. “Is my child bad?” “What does this mean for her future?” “What are the other parents thinking about my family?” Instead sort the specific factors of the situation into what you can and cannot control. You can do this by drawing two circles on a sheet of paper and listing all influencing factors in a column. Factors can be as vague as “who attends your daughter’s school” to the specific, “what was the last thing I said to my child when I dropped her off at school”. The circles of control activity encourages taking responsibility for what you can control, while letting go of uncontrollable factors. It encourages accountability without martyrdom. Ask for help Finding out your sweet child has been acting aggressively can trigger feelings of shame and confusion. These uncomfortable feelings might encourage you to stay quiet, and to hide the problem from those who love and support you. Try to approach the situation by thinking of a forest ecosystem. Your daughter, you, other kids at her school, school staff, and other supportive people are all in this together. You will all thrive and feel better when there is resolution, just like the plants and animals thrive together in a peaceful forest. You may be surprised who else has experienced a similar situation when you make yourself open to receiving support. Fear, anxiety, and stress are all related emotional and psychological responses to perceived threats or challenges, but there are important differences between them. Fear is a natural and immediate emotional response to a real or perceived threat. It is a normal response to danger and is often accompanied by physical sensations, such as increased heart rate, rapid breathing, and sweating. For example, if you hear a loud noise in the middle of the night, you may feel fear because you perceive a potential threat. Anxiety, on the other hand, is a more diffuse and generalised emotional response to perceived threats or challenges. It often involves a sense of uncertainty or apprehension about future events or situations. Anxiety can be triggered by a wide range of stimuli, and it may manifest as physical symptoms such as restlessness, fatigue, or muscle tension. Stress is a physiological and psychological response to challenging or demanding situations. It is a normal response to situations that require increased effort, such as work deadlines or public speaking. However, chronic or prolonged stress can have a negative effect on physical and mental health. PERCEIVED THREAT OR CHALLENGE Fear = Immediate response to actual or perceived danger. ⬇️ Anxiety = Diffuse and general feeling of unease or apprehension ⬇️ Stress = Physiological and psychological response to demands or pressures In summary, understanding the differences between fear, anxiety, and stress can help individuals more effectively recognize and develop strategies to manage and cope with each one. Additionally, by recognising the signs and symptoms of these responses, individuals can seek appropriate treatment or support when necessary. Overall, understanding the differences between fear, anxiety, and stress is an important step in promoting emotional and psychological well-being. |

Categories

All

|

Hopscotch & HarmonyAt Hopscotch & Harmony Psychology, you can expect compassionate care and evidence-based guidance on your journey to wellness.

With clinics in Werribee and Belmont, as well as providing online counselling to clients who live throughout Australia, our dedicated team of psychologists and dietitians are committed to providing support to children, teenagers and adults. With a focus on understanding your unique needs, we offer tailored solutions to foster growth and resilience. Trust in our experience and dedication as we work together towards your well-being. Welcome to a place where healing begins and possibilities abound. |

Our services |

Contact usHopscotch & Harmony

Child, Teen and Adult Psychology Our Locations:

WERRIBEE: 1/167-179 Shaws Rd

BELMONT: 92 Roslyn Rd AUSTRALIA-WIDE: Online counselling |

Hopscotch and Harmony respectfully recognise the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people as the first Peoples of the continent now called Australia.

We acknowledge the Bunurong and Wadawurrung people of the Kulin Nation, the traditional owners of the land on which we work, and pay our respects to their Elders, past, present and emerging.

© 2024 Hopscotch and Harmony Pty Ltd

RSS Feed

RSS Feed