|

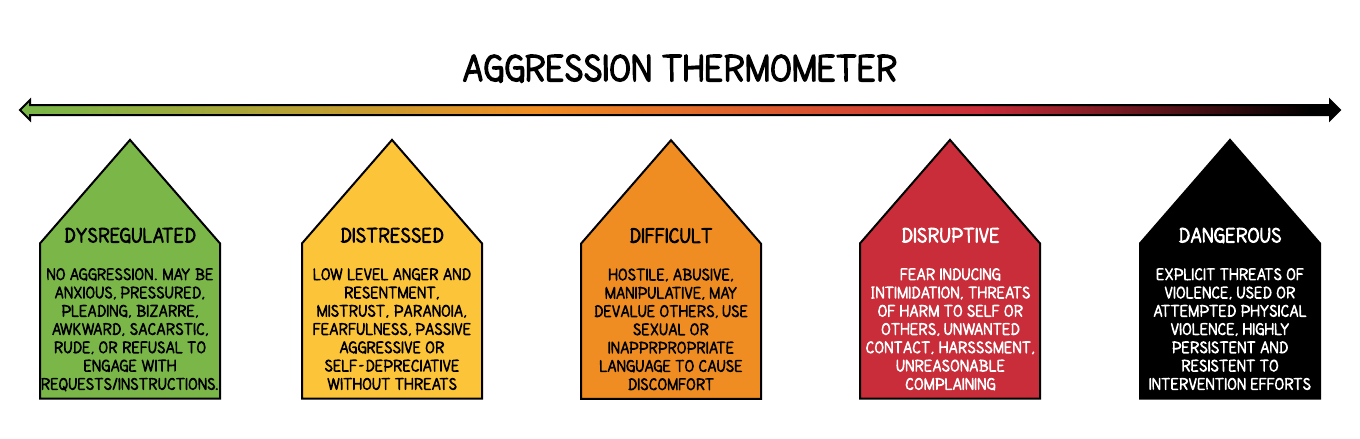

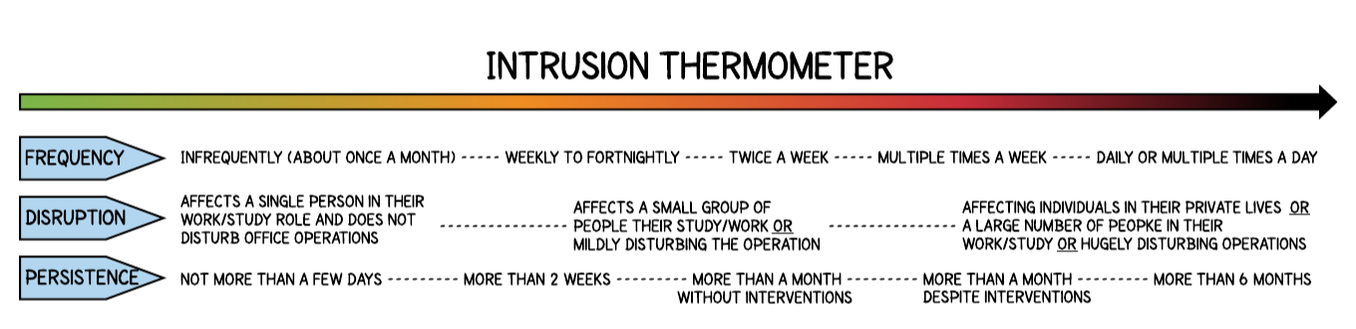

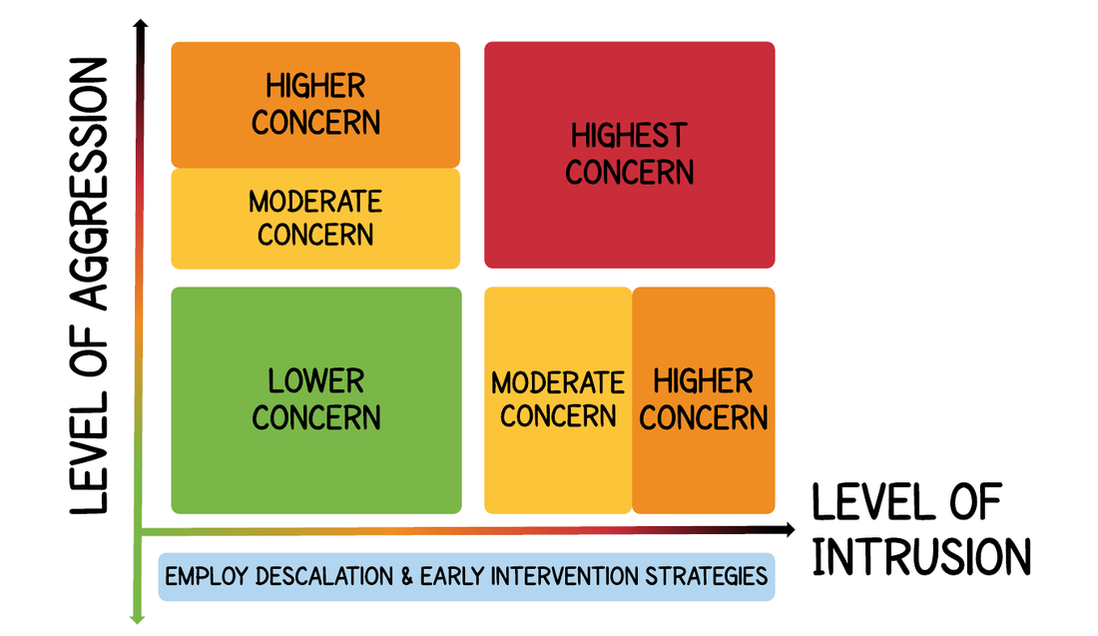

Dr Annabel Chan, Clinical Psychologist In our last blog post, With great bandwidth comes great responsibility: Parenting in the digital age, we learned the internet can - and has - been harnessed for both good and evil. Even so, children and teenagers needn’t miss out on the connections, collaborations, creativity, and communities the internet has to offer simply because of social challenges and potential victimisation online. Instead, equip them (and yourself!) with emotional and practical tools for recognising online dangers, behavioural warning signs, and compromised privacy, and provide them with the language and confidence to collaborate with you to provide a supportive response for concerns and troubles they may have encountered online. So, what can you do if your child discloses that they have been a target of online harm? Validate their worries With the best intentions, worried parents may remove their children's access to the internet as a solution to online victimisation. Unfortunately, that is like telling a child to stop visiting the playground and isolate themselves from peer relationships because they have been bullied. A child who has been the target of online harm does not need to be punished or isolated further! Sometimes, we unconsciously make victims responsible for being attacked, instead of looking to the attacker (“victim-blaming”). This is especially true with online harm, where people speaking up about being hurt on the internet are often dismissed as oversensitive, or “drama queens” who can’t take a joke. Avoid that type of disempowering narrative - whoever came up with “sticks and stones will break my bones, but words will never hurt me” clearly forgot that “the pen is mightier than the sword”! Instead, listen and be willing to learn. Encourage children to discuss their online experiences, and especially their fears and requests for help. Don’t be afraid to admit you don’t fully understand the social media or video games they’re into, if it’s unfamiliar. Do some good old show and tell: ask your child to explain and demonstrate how it works and how they are being harmed. For example, instead of forcing a child to delete Snapchat from their phone, say something like “You’re an expert at Snapchat, but I’m an expert in keeping you safe. How about you teach me how to use Snapchat so we can figure out how we can protect you?” Record your concerns If a child is being subjected to serious harm online, an official report to external authorities may be warranted. However, in order for police, school administrators, or clinicians to act on reports, they need some record of what has happened, and how someone was affected (sometimes known as a “victim impact” statement). Parents can support this process by helping young people keep a timeline of events they felt were harmful, and a record of screenshots as evidence. A common dilemma for parents is wondering when online harm is serious enough to report. Should they be concerned if their daughter is receiving weekly messages from a stranger telling her she’s pretty? Is a boy asking her for nude pictures just being cheeky, because “boys will be boys*”? How worried should parents be if their child is upset because someone on Xbox threatened to kill his family after losing a game? (* Regardless of a parent’s personal values or experiences, the answer is no, no, no! Bad behaviour is not excused by anyone’s gender or situation.) TOOL TIME The threat of online harm can seem confusing and overwhelming, but there’s a way to put in perspective - measure it! One way to do that is using a tool called such as the QuAIC*, which needs two pieces of information about online behaviour: how aggressive it is, and how intrusive. Using the thermometers below, we can place online harm into a box to get a general idea of how concerning it is. (* The Quadrants of Aggression and Intrusion Concern (QuAIC) framework was developed by clinical and forensic psychologists, Dr Annabel Chan and Dr Troy McEwan, as a way for non-clinicians to easily communicate their level of concern for difficult to dangerous behaviours in the workplace and community.) Anyone can use the QuAIC, but there’s a bit more to it than we can put into a blog post. To get some training and practice, go the bottom of this post and make a booking to learn some more about it! Using a tool like this with your child can empower them to understand when their spidey senses should be tingling when interacting with others online (and offline!), and validate their concerns, as many children choose not to tell adults about online experiences that worry them, in case adults won’t take it seriously, or think it’s the child’s fault. Approaching concerns about online risks in a systematic way can also help children to realise if they are victimising others online. Help them understand the roles they may play in online bullying - Are they the one who bullies? The one bullied? The one who assists? The one who reinforces a bully? The one who defends? Or a passive bystander? Parents have a key role in participating in the online experiences of their child and guiding them to be upstanding digital citizens. Buffering - not the Netflix kind Parents have a range of options for preventing an unpleasant online experience becoming traumatic for a child, by placing protections around their communication and sharing the burden of dealing with unwanted communications. For example, if your child is receiving persistent unwanted contact via email, set the email account up to direct all emails from that particular address to be sent straight to you (all email services provide this option). That way, parents can monitor their child’s email traffic and document important details in case a report needs to be made to a school or even the police. Meanwhile, the child is spared the ongoing anxiety of having to deal with the incoming messages. If the harm is happening on a social media platform, such as Facebook, Instagram, etc, help your child block or mute the contact or establish a new profile and review the available privacy settings together, carefully choose which peers and pages to be linked with. Parents can then take over the profile that is being targeted, without their child suffering online social isolation. In cases where a child is being stalked by someone known to her peer groups, it may be helpful to assist her in enlisting the help of their friends to keep the new online profile private. And remember: always seek professional advice - from the police, a threat management specialist, or forensic psychologist - before any direct or indirect interactions with nasty people online, as some responses may increase the risks if not carefully used. An effective safety management plan involves a coordinated approach with school administrators and external professionals trained in assessment and management of problem behaviours. Report and support In Australia, online victimisation can be reported to:

The Office of the eSafety Commissioner website is a gold mine for parents. It contains resources on reporting online harassment, information sheets about online behaviours, and simple guides to privacy settings for most social media and gaming platforms. These resources may also be helpful for parents:

Anyone being targeted with online aggression may experience deterioration of their mental health from the ongoing fear and trauma of not knowing when and where their attackers may return. They may feel guilt or shame if others blame them for getting themselves into these situations. If your child is becoming withdrawn, anxious, or depressed, finding a therapist who is skilled in social media behaviours can be helpful in providing a safe space to debrief and develop coping skills. Supporting a child can also take a toll on the wellbeing of parents, especially if they feel uncertain about how best to navigate the digital frontier. Consider seeking your own therapeutic support or having joint sessions with your child with a therapist who can help you both to regain control of cyberspace and go back to happily watching cat videos again. Hopscotch and Harmony has psychologists with expertise in online harm who can support families through behavioural problems and victimisation in the cyber realm. Contact us to make an appointment or to learn more about how to prevent and respond to online harm and/or register your interest for our The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly of Parenting in the Digital Generation workshop.  Dr Annabel Chan is a forensically-trained Clinical Psychologist and threat assessment & management specialist with expertise in social media dynamics, attachment and identity formation, and behavioural problems in children and adolescents. A skilled navigator of cyberculture and online social behaviour, Annabel enjoys helping her clients and their parents get the most out of communication technology and recognise its strengths and dangers. Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

|

Hopscotch & HarmonyAt Hopscotch & Harmony Psychology, you can expect compassionate care and evidence-based guidance on your journey to wellness.

With clinics in Werribee and Belmont, as well as providing online counselling to clients who live throughout Australia, our dedicated team of psychologists and dietitians are committed to providing support to children, teenagers and adults. With a focus on understanding your unique needs, we offer tailored solutions to foster growth and resilience. Trust in our experience and dedication as we work together towards your well-being. Welcome to a place where healing begins and possibilities abound. |

Our services |

Contact usHopscotch & Harmony

Child, Teen and Adult Psychology Our Locations:

WERRIBEE: 1/167-179 Shaws Rd

BELMONT: 92 Roslyn Rd AUSTRALIA-WIDE: Online counselling |

Hopscotch and Harmony respectfully recognise the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people as the first Peoples of the continent now called Australia.

We acknowledge the Bunurong and Wadawurrung people of the Kulin Nation, the traditional owners of the land on which we work, and pay our respects to their Elders, past, present and emerging.

© 2024 Hopscotch and Harmony Pty Ltd

RSS Feed

RSS Feed